Sleepy Hollow Cemetery

| Sleepy Hollow Cemetery | |

|---|---|

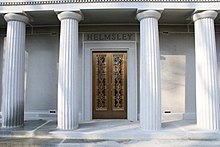

Main entrance to Sleepy Hollow Cemetery | |

| |

| Details | |

| Established | 1849 |

| Location | 540 N. Broadway, Sleepy Hollow, New York |

| Coordinates | 41°05′48″N 73°51′41″W / 41.0966218°N 73.8614183°W |

| Size | 90 acres (36 ha)[1] |

| No. of interments | approx. 45,000[2] |

| Website | Official website |

| Find a Grave | Sleepy Hollow Cemetery |

| The Political Graveyard | Sleepy Hollow Cemetery |

| Area | approx. 85 acres (34 ha)[2] |

| NRHP reference No. | 09000380[3] |

| Added to NRHP | June 3, 2009 |

Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Sleepy Hollow, New York, is the final resting place of numerous famous figures, including Washington Irving, whose 1820 short story "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" is set in the adjacent burying ground of the Old Dutch Church of Sleepy Hollow. Incorporated in 1849 as Tarrytown Cemetery, the site posthumously honored Irving's request that it change its name to Sleepy Hollow Cemetery. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2009.[2]

History

[edit]The cemetery is a non-profit, non-sectarian burying ground of about 90 acres (36 ha).[1] It is contiguous with, but separate from, the churchyard of the Old Dutch Church, the colonial-era church that was a setting for "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow". The Rockefeller family estate (Kykuit), whose grounds abut Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, contains the private Rockefeller cemetery.

In 1894 under the leadership of Marcius D. Raymond, publisher of the local Tarrytown Argus newspaper, funds were raised to build a granite monument honoring the soldiers of the American Revolutionary War buried in the cemetery.[4][5]

Notable monuments

[edit]

The Helmsley mausoleum, final resting place of Harry and Leona Helmsley, features a window showing the skyline of Manhattan in stained glass. It was built by Mrs. Helmsley at a cost of $1.4 million in 2007. She had her husband's body moved from its resting place in Woodlawn Cemetery (Bronx, New York) to the new mausoleum.[6][7]

Notable burials

[edit]

Numerous notable people are interred at Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, including:[1]

- Viola Allen (1867–1948), actress[8]

- John Dustin Archbold (1848–1916), a director of the Standard Oil Company

- Elizabeth Arden (1878–1966), businesswoman who built a cosmetics empire[9]

- Brooke Astor (1902–2007), philanthropist and socialite[10]

- Vincent Astor (1891–1959), philanthropist; member of the Astor family

- Leo Baekeland (1863–1944), the father of plastic; namesake of Bakelite

- Robert Livingston Beeckman (1866–1935), American politician and Governor of Rhode Island

- Marty Bergen (1869–1906), American National Champion Thoroughbred racing jockey

- Holbrook Blinn (1872–1928), American actor

- Henry E. Bliss (1870–1955), devised the Bliss library classification system

- Artur Bodanzky (1877–1939), conductor at New York Metropolitan Opera

- Major Edward Bowes (1874–1946), early radio star, he hosted Major Bowes' Amateur Hour

- Alice Brady (1892–1939), American actress

- Andrew Carnegie (1835–1919), businessman and philanthropist;[10] monument by Scots sculptor George Henry Paulin

- Louise Whitfield Carnegie (1857–1946), wife of Andrew Carnegie

- Walter Chrysler (1875–1940), businessman, commissioned the Chrysler Building and founded the Chrysler Corporation

- Francis Pharcellus Church (1839–1906), editor at The New York Sun who penned the editorial "Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus"

- William Conant Church (1836–1917), co-founder of Armed Forces Journal and the National Rifle Association of America

- Henry Sloane Coffin (1877–1954), teacher, minister, and author

- William Sloane Coffin, Sr. (1879–1933), businessman

- Kent Cooper (1880–1965), influential head of the Associated Press from 1925 to 1948

- Jasper Francis Cropsey (1823–1900), landscape painter and architect; designed the now-demolished New York City Sixth Avenue elevated railroad stations

- Floyd Crosby (1899–1985), Oscar-winning cinematographer, father of musician David Crosby

- Daniel Draper (1841–1931), meteorologist

- Geraldine Rockefeller Dodge (1882–1973), heiress and patron of the arts

- William H. Douglas (1853–1944), U.S. Representative from New York from 1901 to 1905.

- Maud Earl (1864–1943), British-American painter of canines

- Parker Fennelly (1891–1988), American actor

- Malcolm Webster Ford (1862–1902), champion amateur athlete and journalist; brother of Paul, he took his own life after slaying his brother.

- Paul Leicester Ford (1865–1902), editor, bibliographer, novelist, and biographer; brother of Malcolm Webster Ford by whose hand he died

- Dixon Ryan Fox (1887–1945), educator and president of Union College, New York

- Herman Frasch (1851–1914), engineer, the Sulphur King

- Samuel Gompers (1850–1924), founder of the American Federation of Labor

- Madison Grant (1865–1937), eugenicist and conservationist, author of The Passing of the Great Race

- Moses Hicks Grinnell (1803–1877), congressman and Central Park Commissioner

- Walter S. Gurnee (1805–1903), mayor of Chicago

- Angelica Hamilton (1784–1857), the older of two daughters of Alexander Hamilton

- James Alexander Hamilton (1788–1878), third son of Alexander Hamilton

- Robert Havell, Jr. (1793–1878), British-American engraver who printed and colored John James Audubon's monumental Birds of America series, also painter in the style of the Hudson River School

- Mark Hellinger (1903–1947), primarily known as a journalist of New York theatre; producer of The Naked City, a 1948 film noir and namesake of the Mark Hellinger Theatre in New York City

- Harry Helmsley (1909–1997), real estate mogul who built a company that became one of the biggest property holders in the United States, and his wife Leona Helmsley (1920–2007), in a mausoleum with a stained-glass panorama of the Manhattan skyline. Leona famously bequeathed $12 million to her dog.

- Eliza Hamilton Holly (1799–1859), younger daughter of Alexander Hamilton

- Raymond Mathewson Hood (1881–1934), architect[1]

- William Howard Hoople (1868–1922), a leader of the nineteenth-century American Holiness movement; the co-founder of the Association of Pentecostal Churches of America, and one of the early leaders of the Church of the Nazarene

- Washington Irving (1783–1859), author of "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" and "Rip Van Winkle"

- William Irving (1766–1821), U.S. Congressman from New York

- George Jones (1811–1891), co-founder of The New York Times

- Albert Lasker (1880–1952), pioneer of the American advertising industry, part owner of baseball team the Chicago Cubs, and wife Mary Lasker (1900–1994), an American health activist and recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom and the Congressional Gold Medal

- Walter W. Law, Jr. (1871–1958), lawyer and politician, son of Briarcliff Manor founder Walter W. Law

- Lewis Edward Lawes (1883–1947), reformist warden of Sing Sing prison

- William E. Le Roy (1818–1888), United States Navy rear admiral

- Ann Lohman (1812–1878), a.k.a. Madame Restell, 19th century purveyor of patent medicine and abortions

- Charles D. Millard (1873–1944), member of U.S. House of Representatives from New York

- Darius Ogden Mills (1825–1910), made a fortune during California's gold rush and expanded his wealth further through New York City real estate

- Belle Moskowitz (1877–1933), political advisor and social activist

- Robertson Kirtland Mygatt (1861–1919), noted American landscape painter, part of the Tonalist movement in Impressionism

- N. Holmes Odell (1828–1904), U.S. Representative from New York

- George Washington Olvany (1876–1952), New York General Sessions Court judge and leader of Tammany Hall

- William Orton (1826–1878), President of Western Union[11]

- Peter A. Peyser (1921–2014), served as a Member of Congress from New York from 1971 to 1977 as a Republican and from 1979 to 1983 as a Democrat

- Whitelaw Reid (1837–1912), journalist and editor of the New-York Tribune, vice-presidential candidate with Benjamin Harrison in 1892, defeated by Adlai E. Stevenson I; son-in-law of D.O. Mills

- William Rockefeller (1841–1922), New York head of the Standard Oil Company[10]

- Edgar Evertson Saltus (1855–1921), American novelist

- Francis Saltus Saltus (1849–1889), American decadent poet & bohemian

- Carl Schurz (1820–1906), senator, secretary of the interior under President Rutherford B. Hayes and namesake of Carl Schurz Park in New York City

- Charles Sheeler (1883–1965), painter and photographer, and his wife Musya (1908–1981), photographer, are buried together.

- William G. Stahlnecker (1849–1902), U.S. Representative from New York

- Egerton Swartwout (1870–1943), New York architect

- William Boyce Thompson (1869–1930), founder of Newmont Mining Corporation and financier

- Joseph Urban (1872–1933), architect and theatre set designer

- Henry Villard (1835–1900), railroad baron whose monument was created by Karl Bitter.[12]

- Oswald Garrison Villard (1872–1949), son of Henry Villard and grandson of William Lloyd Garrison; one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

- William A. Walker (1805–1861), U.S. Representative from New York

- Paul Warburg (1868–1932), German-American banker and early advocate of the U.S. Federal Reserve system.

- Worcester Reed Warner (1846–1929), mechanical engineer and manufacturer of telescopes

- Thomas J. Watson (1874–1956), transformed a small manufacturer of adding machines into IBM

- Theodore Whitmarsh (1869–1936), administrator of the United States Food Administration, director of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York

- Hans Zinsser (1878–1940), microbiologist and a prolific author

In popular culture

[edit]Several outdoor scenes from the feature film House of Dark Shadows (1970) were filmed at the cemetery's receiving vault. The cemetery also served as a location for the Ramones' 1989 music video "Pet Sematary".[13]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Famous Interments". Sleepy Hollow Cemetery. Archived from the original on 2017-10-30.

- ^ a b c "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form" (PDF). National Park Service. 3 June 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 August 2017.

- ^ "National Register Information System – Sleepy Hollow Cemetery (#09000380)". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ "Monument for Sleepy Hollow: Tarrytown to Honor Men Who Fought is the Revolution". The New York Times. July 1, 1894.

- ^ "Tarrytown Heroes Honored: Beautiful Shaft Dedicated in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery. War Ships Boom Salutes, Thousands of Patriotic Americans Look On". The New York Times. 20 October 1894.

- ^ Trotta, Daniel (August 20, 2007). "New York's Helmsley to rest in $1.4 mln mausoleum". Reuters. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ Lombardi, Kate Stone (23 April 2006). "Why Leona Buried Harry Not Once, But Twice". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ "Viola Allen (Viola Emily Allen)". The Early History of Theatre in Seattle. Archived from the original on January 6, 2018.

- ^ Morton, Camilla (2011). A Year in High Heels. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-1-4447-1709-9.

- ^ a b c Keneally, Meghan; Smith, Olivia (12 October 2015). "Take a Tour of the Sleepy Hollow Cemetery". ABC News. Archived from the original on 2018-01-05.

- ^ Reid, James D. (1886). The Telegraph in America and Morse Memorial.

- ^ Dennis, James M. (1967). Karl Bitter: Architectural Sculptor, 1867–1915. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 94–96. ISBN 978-0-5980-9236-6.

- ^ Ramone, Marky (2015). Punk Rock Blitzkrieg. John Blake Publishing. p. 277. ISBN 978-1-78418-830-6.

Bibliography

[edit]- Raymond, Marcius Denison (October 19, 1894). Souvenir of the Revolutionary Soldiers' Monument Dedication, at Tarrytown, N.Y. Rogers & Sherwood. p. 171.

- "Sleepy Hollow Cemetery Monument" (PDF). The New York Times. October 14, 1894.

External links

[edit]- Sleepy Hollow Cemetery

- 1849 establishments in New York (state)

- Buildings and structures completed in 1849

- Cemeteries on the National Register of Historic Places in New York (state)

- Cemeteries in Westchester County, New York

- Historic districts in Westchester County, New York

- Historic districts on the National Register of Historic Places in New York (state)

- National Register of Historic Places in Westchester County, New York

- U.S. Route 9

- Mount Pleasant, New York

- American Revolutionary War sites

- Monuments and memorials in New York (state)

- Cemeteries established in the 1840s