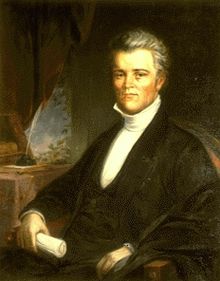

Noah Noble

Noah Noble | |

|---|---|

| |

| Sheriff | |

| In office 1820–1824 | |

| Constituency | Franklin County |

| Indiana House of Representatives | |

| In office December 5, 1823 – December 4, 1824 | |

| Constituency | Franklin County |

| 5th Governor of Indiana | |

| In office December 7, 1831 – December 6, 1837 | |

| Lieutenant | David Wallace |

| Preceded by | James B. Ray |

| Succeeded by | David Wallace |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 15, 1794 Berryville, Virginia, US |

| Died | February 8, 1844 (aged 50) Indianapolis, Indiana, US |

| Political party | Whig |

| Spouse | Catherin Stull van Swearingen Noble |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Branch/service | Indiana Militia |

| Years of service | 1811–1820 |

| Rank | Colonel |

| Commands | 7th Regiment |

Noah Noble (January 15, 1794 – February 8, 1844) was the fifth governor of the U.S. state of Indiana from 1831 to 1837. His two terms focused largely on internal improvements, culminating in the passage of the Mammoth Internal Improvement Act, which was viewed at the time as his crowning achievement. His taxing recommendations to pay for the improvements were not fully enacted, and the project ultimately led the state to negotiate a partial bankruptcy only a few years later. The debacle led to a gradual collapse of the state Whig party, which never regained control of the government, and led to a period of Democratic control that lasted until the middle of the American Civil War. After his term as governor he was appointed to the Board of Internal Improvement where he unsuccessfully advocated a reorganization of the projects in an attempt to gain some benefit from them.

Early life

[edit]Family and background

[edit]Noah Noble was born in Berryville, Virginia, on January 15, 1794, one of fourteen children of Dr. Thomas Noble and Elizabeth Clair Sedgwick Noble. Around 1800, his family moved to the frontier where his father opened a medical practice in Campbell County, Kentucky. In 1807, the family moved again to Boone County where his father acquired a 300-acre (120 ha) plantation which was operated by slave labor. Noble moved to Brookville, Indiana, around 1811 at age seventeen, following his brother James Noble, who had moved there some time earlier. James was a prominent lawyer and later United States Senator.[1]

In Indiana he made several business ventures with his partner Enoch D. John. Together they operated a hotel in Brookville, became heavily involved in land speculation, and opened a water-powered weaving mill with a wool carding machine. Noble also opened a trading company called N. Noble & Company. The company purchased produce from area farmers and shipped it to New Orleans to be sold. In 1819 a boating accident destroyed one of his shipments and left him with a large debt that took several years to repay. Later that year he married his cousin, Catherin Stull van Swearingen. The two shared the same great-grandfather. They had three children, but only one survived into adulthood; two died as infants.[2]

Entry into politics

[edit]Noble entered politics in 1820, winning an election to become Franklin County's sheriff. By the time of his 1822 reelection bid he had become very popular in the county, and he won reelection 1,186 to 9 votes. He was commissioned a lieutenant colonel in the 7th Regiment of the Indiana militia in 1817, and a colonel in 1820. When his term as sheriff expired, he ran to represent the county in the Indiana House of Representatives, winning overwhelmingly. He was reelected again the following year but resigned following the death of his brother Lazarus. Lazarus had been the Receiver of Public Moneys of the Indianapolis Land Office, and his death left a vacancy. His brother, Senator James Noble, used his influence to secure the post for Noble, who remained in the position until 1829. The job took him to Indianapolis, where he was responsible for collecting revenue for the federal government. The position brought him into contact with many of the leading men in the state and he was quick to create good relationships with them. Following the election of President Andrew Jackson and the employment of the spoils system, Noble was removed from the position.[2][3]

Finding himself without a job, Noble launched another business venture. Before he could open the new business, his friends in the Indiana General Assembly appointed him to a commission that was responsible for laying out the Michigan Road. He remained on the commission until 1831, at which time he announced his candidacy for governor of Indiana as a Whig candidate, and secured the Whig nomination.[4]

Governor

[edit]During the campaign, he accused his Democratic opponent James G. Read of being ineligible to run because he was a Federal Receiver. The state constitution forbade state officials from holding both federal and state positions simultaneously. His opponent made a similar charge against Noble, who still held his position as a federal commissioner working on the Michigan Road. Noble campaigned heavily on the internal improvement platform and won the election by a plurality of 23,518 votes to Read's 21,002, with independent Milton Stapp taking 6,894.[4]

After becoming governor he purchased several lots on the eastern edge of the capitol, planting an orchard and vineyard and building a large brick home. He brought some of his father's emancipated slaves with him to work in his household, one of whom was supposedly the model for Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom. She visited Noble's home on more than one occasion.[5]

First term

[edit]

Indiana was continuing to experience a period of prosperity as a large influx of settlers purchased land, thereby providing a large income for the government. Noble's predecessor had begun the framework for the large-scale internal improvements that were to come, but had significantly delayed the start of the canal projects. Noble set to work immediately and within a few months he completed surveying the route of the Wabash and Erie Canal and made several recommendations regarding its construction. Noble was opposed to railroads, which he viewed as monopolies since only the rail company could transport goods on the line, whereas canals were open to anyone had a boat. Construction on the canal began in earnest in 1832.[5]

Construction on state roads was progressing slowly because of a lack of funding. Noble proposed the state borrow money to speed the construction process, but the legislature rejected his proposal. He also recommended the creation of an Internal Improvement Board to coordinate the projects and possibly reduce costs through better organization and purchase of supplies in bulk, but again the General Assembly rejected the proposal, and instead kept the projects operating under several different project boards. His first term passed with little advancement on the internal improvement front because the representatives from southern part of the state blocked any large-scale plans on the grounds that such projects would have little value for their constituents since most of the projects would be in the central part of the state.[5]

Noble had a census conducted and recommended that the legislature reapportion representation to grant more seats to the central counties. The legislature approved the plan, and expanded the Senate and House of Representatives to their present sizes of 50 and 100 seats, respectively. The change gave the central and northern parts of the state more representatives than the south for the first time, despite the fact that the south was still significantly more populous.[5] Noble made several recommendations for the reform of public schools. Most of the measures were not accepted, but the expansion of the Indiana College was approved, and township schools were granted considerably more power over their own operations.[6]

The Second Bank of the United States was closed during Noble's first term, leaving the state without a bank to hold government deposits or to supply paper money. There had been no banks operating in Indiana for a decade, so with no alternative to the situation the General Assembly passed a bill to create the Bank of Indiana. Noble had not taken a position on the bill, but signed it into law. The bank eventually turned out to be very profitable and one of the most important acts of his time in office.[6] Noble also oversaw the creation of plans to build Indiana's third statehouse in 1831. The building was completed in 1835, and he also oversaw the move of the government's offices.[7]

Second term

[edit]

Noble was re-elected in 1834, campaigning against James G. Read for a second time. During the campaign, Noble sold a Kentucky slave that belonged to his father. The account was widely published, and turned the anti-slavery elements in the state against him, demonstrating by his receiving only 28 votes from the Quaker-dominated eastern counties of the state.[8] He ultimately won the election, 27,767 to 19,994 votes. Noble called out the militia in parts of the state when it was threatened during the Black Hawk War, a Native American uprising to the west of Indiana. 150 men were sent to Illinois, where they skirmished with the native uprising.[9] The scare was only brief, and the focus soon returned to the internal improvements.

With the legislature closely divided on the issue, additional projects were proposed for the southern areas of the state to gain the support of their representatives. All the projects were bundled into one bill and passed as the Mammoth Internal Improvement Act in 1836. The act caused a great deal of celebration in the state and Noble considered the act his greatest achievement at the time. To pay for the act, which was projected to cost $10 million, Noble had also recommended a 50% increase in all state taxes. However, the legislature failed to pass that measure.[10]

The Panic of 1837 hit the following year, causing a sharp decrease in tax revenues, even as the state budget was already faced a large deficit because of the interest on the debt. Property taxes were the state's primary regular income, and to increase the revenue Noble proposed that the tax be levied ad valorem. The change would save the state a significant amount in administrative and collection costs, and make more land subject to taxation. The tax was approved and led to a 25% increase in revenue the following year, but it was still not enough to cover the deficit. Noble proposed the projects be prioritized, and work halted on the less important ones to conserve funds, but the plan was rejected. By the time Noble left office, the state's financial situation was bleak, but it was not yet fully apparent that far more had been borrowed than could be paid back. Despite the dire situation, Noble left office in 1837 as a popular political figure and was able to use his prestige to help elect David Wallace, his lieutenant governor, as governor.[10]

In both 1834 and 1836, Noble had his name entered as a candidate for the United States Senate, but in both years the legislature decided to send someone else to Congress, much to Noble's disappointment.[11]

Later life

[edit]State bankruptcy

[edit]After leaving office Noble became a member of the Board of Internal Improvements which was tasked with overseeing the ongoing internal improvements in the state. In 1840, the state ended all funding for the projects. By early 1841 it was clear that the state would not be able to pay even the interest on its debt, and paying it off was out of the question. The board approved the sending of James Lanier to negotiate a bankruptcy with the state's creditors, and all the internal improvement projects, except the separately funded Wabash and Erie Canal, were turned over to the creditors in exchange for a 50% reduction in the state's debt.[11]

Death and legacy

[edit]

Even before Noble had left office, many of his opponents began to blame him for the state's financial situation. He argued that he had proposed tax increases to fund the project, and it was the fault of the General Assembly for not enacting them. Although the short term situation was devastating to the state and many of the projects were never completed, the groundwork laid by the projects led to rapid development after the financial situation was resolved. In the meantime, the debacle became apparent to the public during his successor's term and led to the gradual collapse of the state's Whig party, which never regained power in Indiana. In the immediate years thereafter the Democrats came to power and disposed of all the projects. The situation ultimately led to language in the 1851 constitution prohibiting the state from assuming debt.[11]

Noble returned to private life following the dissolution of the Internal Improvement Board in 1841. The situation was too dire, and opinion too anti-Whig for Noble to have a serious chance of winning public office again. He died at the age of 50 in Indianapolis two years later, on February 8, 1844, and was buried next to his wife, Catharine, in Greenlawn Cemetery. His body was moved to Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis on July 14, 1874.[11][12]

Noble County, Indiana is named in his honor,[13] as is Noble Township in Cass County.[14]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

- ^ Gugin, p. 70

- ^ a b Gugin, p. 71

- ^ Woollen, p. 65

- ^ a b Gugin, p. 72

- ^ a b c d Gugin, p. 73

- ^ a b Gugin, p. 76

- ^ Gugin, p. 77

- ^ Woollen, p. 67

- ^ Woollen, p. 68

- ^ a b Gugin, p. 74

- ^ a b c d Gugin, p. 78

- ^ Woollen, p. 66

- ^ De Witt Clinton Goodrich & Charles Richard Tuttle (1875). An Illustrated History of the State of Indiana. Indiana: R. S. Peale & co. pp. 568.

- ^ Helm, Thomas B. (1878). History of Cass County, Indiana. Kingman Bros. pp. 36.

Bibliography

- Gugin, Linda C.; St. Clair, James E, eds. (2006). The Governors of Indiana. Indianapolis, Indiana: Indiana Historical Society Press. ISBN 0-87195-196-7.

- Woollen, William Wesley (1975). Biographical and Historical Sketches of Early Indiana. Ayer Publishing. ISBN 0-405-06896-4.

External links

[edit]- 1794 births

- 1844 deaths

- Burials at Crown Hill Cemetery

- People from Berryville, Virginia

- People from Brookville, Indiana

- Members of the Indiana House of Representatives

- Politicians from Indianapolis

- Governors of Indiana

- Indiana Whigs

- Whig Party state governors of the United States

- Indiana sheriffs

- 19th-century American businesspeople

- Businesspeople from Indiana

- 19th-century members of the Indiana General Assembly