Harrisburg, Illinois

Harrisburg | |

|---|---|

City | |

| City of Harrisburg | |

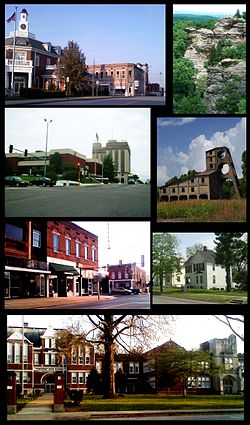

From top left: Northern side of square, Garden of the Gods, Saline County Courthouse and Clearwave Building, O'Gara mine tipple, southern side of square, Poplar Street homes, Harrisburg Township High School | |

| Nickname(s): The Burg, H-burg | |

| Motto: Gateway to the Shawnee National Forest | |

Location of Harrisburg in Saline County, Illinois | |

| Coordinates: 37°44′02″N 88°32′45″W / 37.73389°N 88.54583°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Illinois |

| County | Saline |

| Settled | 1847 |

| Founded | 1853 |

| Incorporated | 1889 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | John McPeek |

| Area | |

| • Total | 6.81 sq mi (17.63 km2) |

| • Land | 6.61 sq mi (17.12 km2) |

| • Water | 0.20 sq mi (0.51 km2) 3.11% |

| Elevation | 397 ft (121 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 8,219 |

| • Density | 1,243.04/sq mi (479.97/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 62946 |

| Area code(s) | 618, 730 |

| FIPS code | 17-33136 |

| Website | www.thecityofharrisburgil.com |

Harrisburg (/ˈhærɪsbɜːrɡ, ˈhɛərz-/) is a city in and the county seat of Saline County, Illinois, United States.[2] It is located about 55 miles (89 kilometers) southwest of Evansville, Indiana, and 111 mi (179 km) southeast of St. Louis, Missouri. Its 2020 population was 8,219, and the surrounding Harrisburg Township had a population of 10,037, including the city residents. Harrisburg is included in the Illinois–Indiana–Kentucky tri-state area and is the principal city in the Harrisburg micropolitan statistical area with a combined population of 24,913.[3]

Located at the concurrency of U.S. Route 45, Illinois Route 13, Illinois Route 145, and Illinois Route 34, Harrisburg is known as the "Gateway to the Shawnee National Forest",[4] and is also known for the Ohio River flood of 1937, the old Crenshaw House (also known as the Old Slave House), the Tuttle Bottoms Monster, prohibition-era gangster Charlie Birger, and the 2012 EF4 tornado. A Cairo and Vincennes Railroad boomtown, the city was one of the leading bituminous coal-mining distribution hubs of the American Midwest between 1900 and 1937.

At its peak, Harrisburg's population reached 16,000 by the early 1930s. The city had one of the largest downtown districts in Southern Illinois.[5] The city was the 20th-most populated city in Illinois outside the Chicago metropolitan area and the most-populous city in Southern Illinois outside the Metro East in 1930.[6] However, the city has seen an economic decline due to the decreased demand for high-sulfur coal, the removal of the New York Central railroad, and tributary lowlands leaving, much area around the city unfit for growth due to flood risks.

History

[edit]Pioneer and native coexistence

[edit]At the beginning of recorded American history, the Harrisburg area was inhabited by several Algonquian tribes, including the Shawnee and Piankashaw, who lived in the dense inland forests. Prior to the arrival of European settlers, the Piankashaw tribe was driven out by the more aggressive Shawnee. European settlement in Illinois began with the French from 1690 and reached its peak about 1750, mainly along the Mississippi River. American settlers arrived in 1790. The French came as merchants and missionaries, with farming supplementing the need for trade. The result had benefited both the settlers and the Native Americans. The American migration, however, followed treaties which resulted in land being distributed through American Law, ignoring previous indigenous rights. Encroachment ensued and caused hard feelings between the Indians and the settlers who moved into the interior and along migration routes. Many of the Indians allied themselves with the British to resist, though trade with the Americans was an important reason why the Native Americans remained largely peaceful.[7]

The town of Harrisburg was platted a few miles south of the junction of the Goshen and Shawneetown–Kaskaskia Trail, two of the first pioneer trade routes in the state. Prior to the War of 1812, most of the population of today's Saline County lived in cabins clustered around blockhouses to protect against Indian attack and dangerous wildlife such as cougars and bears. Permanent settlements in the forested area were inevitable with the influx of more settlers, and the first land entry was made in 1814 by John Wren and Hankerson Rude. By 1840 the settlers outnumbered the Native Americans, and most of the black bear population of the county had been killed off by 1845.[7]

Founding

[edit]Harrisburg was plotted shortly after Saline County was established in 1847 from part of Gallatin County. The city was named for James Alexander Harris, who had built a farmhouse and planted a corn field in a clearing in the area of the current city square around 1820.[8]

Harris along with John Pankey, James P. Yandell, and John X. Cain, donated land for the first additions of the town to a special committee at Liberty Baptist Church in 1852, after complaints that the county seat should be centralized in the county. The county seat then was in Raleigh. The county's two main population centers were divided by the Saline River and 14 miles (23 km) of thicket. There were no roads in the county and many residents from the areas of Carrier Mills and Stonefort became lost when traveling to the northern settlements of Raleigh, Galatia, and Eldorado. The designated town plat was considered due to its aesthetic properties, a 60-foot (18 m) sandstone bluff overlooking the Saline River valley called "Crusoe's Island". Although it was heavily timbered with oak and hickory with an impenetrable hazel underbrush, the site was at the geographical center of the county. A major legal battle took place within the county government because of voter fraud accusations by the people of Raleigh.[8] Nevertheless, Harrisburg was plotted as a village on 20 acres (10 ha) in 1853 and became the county seat in 1859.

Industrial origins

[edit]

Between 1860 and 1865 southern cotton became unavailable during the Civil War, Harrisburg was one of the few cities in the Upland South during this time to have woolen mills, making the town an industrial asset early on to Southern Illinois. Several planing mills and flour mills also dotted the city.[9] The Cairo and Vincennes Railroad was completed in 1872 by Ambrose Burnside, and American Civil War, Union Army, brigadier general Green Berry Raum, who was living in Harrisburg at that time.[4]

Robert King, an early proprietor, opened a brick and tile factory at the southern terminus of Main Street in 1896 with the capacity of carrying out 15,000 bricks every 10 hours. Harrisburg also saw the opening of several saw mills. The Snellbaker and Company Saw Mill and Lumber Yard opened in 1895, as well did J.B. Ford Harrisburg Planing Mill the same year. The mill had the capacity of producing 10,000 board feet (23.6 m3) of lumber every 10 hours. The Barnes Lumber Company in Harrisburg started as a sawmill operation in 1899. Since 1904 it has retailed a complete line of lumber and building materials and is the oldest, currently active mill in the city.[10]

The Woolcott Milling Company, operated by J.H. Woolcott and J.C. Wilson built a flour mill in 1874, on the now defunct south Woolcott Street, with rail spur, behind the current Parker Plaza, that had 23 grain elevators and the capacity of carrying out 200 barrels of flour in a 24-hour period and up to 400 by 1907, with a new 75,000-US-bushel (2,600,000 L) tower. The exchange market was located in Carrier Mills.[10] Located on Commercial Street across the tracks from the train depot, The Southern Illinois Milling & Elevator Company was incorporated on July 29, 1891, by Philip H. Eisenmayer, with a capital stock of $50,000. The company had two elevators, erected at a cost of $125,000, one of which had a capacity of 25,000 US bushels (881,000 L) and the other a capacity of 100,000 bushels. Their milling capacity was six hundred barrels per day. Twenty-five men were employed in the operations of the mill and elevators, in addition to a force of from six to eight men regularly employed in the cooperage department.[11]

During the Reconstruction Era, when economic conditions made impractical the growing of cotton, lumbering and tobacco growing (which pioneers found profitable commercially), grain farming by crop rotation, dairying, reforestation, merchandising and manufacturing, and Coal mining especially, began to occupy the city.[12] In 1889, with a population of 1,500, Harrisburg became a city, with an aldermanic form of government. It adopted the commission form in 1915.[4] Despite these early industrial advantages over other cities in the region, the Sanborn Map Company still referred to the water facilities and road conditions within the city limits, "Not good, and not paved" up to 1900.[10]

Coal and rail era

[edit]

First slope mine operations began in 1854 southeast of Harrisburg. During the early years, the coal was transported by wagon to local homes and businesses for heating. Coal Mining became an important industry for the post-Antebellum, now Gilded Age city.[4] The Cairo and Vincennes Railroad was completed in 1872 and provided transportation for coal and the miners who tired away underground.[4] After a series of corporate transactions brought the Cairo and Vincennes Railroad into the hands of the Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago & St. Louis Railway around 1890, with Illinois state representative Charles P Skaggs as mayor,[13] Harrisburg evolved into one of the leading coal-mining centers of the Midwest.[5] Harrisburg was a strategic spot on the railroad route with a large hump yard, making it the focal point for the most productive coal field operations. Some of the most profitable coal companies that operated around Harrisburg were Big Creek Coal, Harrisburg Coal and O'Gara Coal. Each one with their own sizable rail yards.[5] O'gara was a Progressive Era coal company owned by Thomas J. O'gara of Chicago. He purchased and annexed 23 privately owned mines in the Harrisburg coal field which equaled 50,000 acres (200 km2) of land.[14] The Company based its headquarters in Harrisburg in 1905. O'gara only owned 12 operating mines, all in Saline County, but they had an annual output of 7,000,000 tons. 6,000 men were employed in a field capacity and the pay roll disbursement was $150,000 per month. The company paid $10,000 monthly royalty. H. Thomas was the company's general manager of mines, Ed Ghent its chief engineer and D. B. McGehee the assistant general manager.[15]

By 1905, several small slope mines and 15 shaft mines operated in the county. Most were along the railroad line. Large numbers of immigrants from England, Wales, and eastern Europe, looking for work, detrained at the Harrisburg Train Depot; crowding around quickly expanding mining villages directly outside the city, such as Muddy, Wasson, Harco and Ledford. The city's population quickly expanded from 5,000 to 10,000 in a few years.[5] By 1906, the Big four/CCC&STL Railroad became the New York Central,[5] and Saline County was producing more than 500,000 tons of coal annually with more than 5000 miners at work.[4] In 1915 the Ringling Brothers Circus made an appearance in Harrisburg.[16] In 1913, the Southern Illinois Railway and Power Company operated an interurban trolley line, that ran from downtown Eldorado, into Muddy, Wasson, Beulah Heights, through downtown Harrisburg, Dorrisville, Ledford and into downtown Carrier Mills, all of which had larger residential areas than present.[17] In 1917 there were plans to extend the line westward to Marion and Carbondale to connect to the Coal Belt Co. line, and then run it towards St. Louis.[18] The trolley wire through the county was 16 feet (5 m) high.[8] It was an off branch of the Cairo and Vincennes Railroad. The corporation erected the first electrical generating plant in Muddy, Illinois.[17]

The Central Illinois Public Service Company purchased the Muddy Power Station in 1916. It had a generating capacity of 7,500 kilowatts. After removing an original 2,500-kilowatt unit, the company added two 5,000-kilowatt turbine-generators and one 10,000 kilowatt unit, bringing the stations total capacity to 25,000 kilowatts in 1922. Electricity generated at the station was distributed over 66-kv, double circuit steel tower transmission lines extending to West Frankfort to the west, the Ohio River to the east, and Olney to the north. The plant had two impounding reservoirs which covered 80 acres (32 ha) and held 320 million gallons of water.[8]

The community benefited from the prosperity of the Roaring Twenties, flaunting the most extravagant displays of wealth in the city's history. The 230-foot (70 m) neon red tower belonging to the WEBQ-A.M. radio station was the tallest structure in the city and could be seen for miles.[9] Harrisburg had just finished the new three-story Horning Hotel around 1920, and two new theaters with a combined total of 1,600 seats: the Orpheum and the Grand the same year. The eight-story Harrisburg National Bank building, the O'Gara Coal Headquarters, the Cummins Office building, and the four-story Harrisburg Hospital were all built in 1923. The new four-story Harrisburg City Hall building was constructed in 1927, and a complex highway system was constructed through the city, with Illinois Route 13 and Illinois Route 34 constructed in 1918; U.S. Route 45 and Illinois Route 145 constructed in 1925–1926. During this time the city expanded to 15,000 people. The annexation of Dorrisville and Dorris Heights created blue collar, multiple, and single family homes filling in between.[19] On Vine Street south of the town square was "Wiskey Chute", a saloon vice district for local miners.[13] It was also during this time that the town was home to prohibition-era bootlegger Charles Birger, whose gang was said to have protected local business owners better than the law enforcement. For a time, the gangster's prized Tommy gun was displayed in a glass case in the City Hall.[16] The geography around Harrisburg changed indefinitely, with coal areas producing a surface mining landscape the size of San Jose, California, roughly 172 sq mi (450 km2),[20] aptly named the Harrisburg Coal Field. The field completely encased the towns of Carrier Mills and Harrisburg, while creating partial borders to Stonefort, Galatia, and Raleigh. Near the mines were gob piles that spontaneously combusted. The horizon around the city for many years flickered with burning coal refuse.[9]

Slow economic decline

[edit]Harrisburg reached its peak population of 15,659 in 1930, making it the 20th most populated city outside the Chicago Metropolitan Area, in Illinois, and the most populous city in Southern Illinois outside the metro-east. If the city combined the service communities bordering Harrisburg such as Ledford and Muddy, the population would have been even greater at 26,000, and Saline County as a whole reached nearly 40,000 people.[21] Even with the economic downturn during the Great Depression, with business owners and industrial firms closing shop, the city continued to thrive due to its enormous coal industry. On June 17, 1936, Eleanor Roosevelt visited Harrisburg to observe work of the WPA and delivered a speech in the packed high school gymnasium.[22] The heyday ended quickly when the Ohio River flood of 1937 left 4,000 within the city homeless and 80% of the city inundated.[23] Many flooded mines were deemed condemned which left the local economy crippled. In 1938, the state of Illinois had completed one of the largest operations of its kind ever attempted in the United States, the removal of more than two and a half billion gallons of flood water from Sahara mine No. 3.[24]

Soon the Southern Illinois Railway and Power company was bought by the Central Illinois Public Service Company. The inter-urban line was abandoned in 1933 after 20 years of service.[17] After the decommission of the Interurban line, Harrisburg opened the Harrisburg-Dorrisville Bus Co., which was a private predecessor bus company to the current Rides Mass Transit District which was opened in 1980.[19] Between 1930 and 1940 the city lost 27% of its overall population.[25]

Immediately after World War II new coal companies, Peabody, Bluebird, and Sahara, started mining within the city. The war created a great demand for energy, which was satisfied by expanded strip mining operations throughout the Harrisburg Coal Fields. Shortly after World War II, it became clear that coal was losing favor to other energy sources such as oil and natural gas. In contrast to other cities in the United States that prospered in the post-war boom, the fortunes of Saline County began to quickly diminish.[5] Harry Truman stopped briefly in Harrisburg during his whistlestop tour on September 30, 1948, giving some hope for economic recovery for the region. Without hesitating, the long parade of police, buses, and accompanying cars sped through town. Poplar Street, at that time the main drag through town, was crowded with multitudes of persons for its entire length. It was reported by the Daily Register newspaper that cars were lined along Route 13 all the way from Marion and on to Eldorado on Route 45.[19] In 1950 Illinois Assistant State Attorney General George N. Leighton represented parents in a proceeding which desegregated the public schools of Harrisburg.[26] On December 1, 1953, WSIL-TV 3 was founded and based out of the city. The station built the 503 ft (153 m), WSIL tower in downtown which was one of the tallest television towers in the state at the time and is still the tallest structure in the city.

By 1957, the Egyptian was the last passenger train to travel through the city.[19] Between 1940 and 1960 Harrisburg lost another 20% of its population due to economic standstill.[25] With only 9100 people left in the city that once had 16,000, then Senator John F. Kennedy made a campaign stop on October 3, 1960. Speaking at the Saline County Court House he said

"This district, which is built on the land and which has been nourished by the land, personifies the kind of problems which I think the United States is going to face in the 1960s. This district has depended in the main for its resources, its growth, its wealth, upon the minerals underground and upon the food that is grown on the ground. And those are those industries that have faced serious problems in the 1950s."[27]

Later during the same speech, after addressing agriculture, Senator Kennedy stated:

"Farmers could farm and work in the cities and towns, but this year we have the highest unemployment that we have had in any months of August and September, the three Augusts and Septembers preceding the recession of 1949, 1954, and 1958, and this district knows this problem well, because this district has lost 60,000 people in the last 10 years."[27]

By 1968, with hopes of bringing a new influx of coal mining into the city, Sahara Coal Company ordered the Bucyrus-Erie "GEM of Egypt" strip mine shovel, one of the largest in the world at 8 stories high and weighing 1,000 tons.[13] It took three men to operate it, and its bucket capacity was 30 cubic yards. Even with such great efforts coal mining continued to dwindle within the community. The train depot was razed in 1972 and all coal freight was ordered out of the Harrisburg Hump Yard by 1973. During the 1970s and 1980s, many of the city-square storefronts and mini-plazas became vacant and were slowly abandoned as large chain stores and strip malls on Commercial Street became the dominant venues for shopping and entertainment, hoping to bring an influx of travelers from the main highway.[5]

The Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990 legislation forced many utility companies in the United States to switch to low-sulfur coal. In response Harrisburg's already waning economy took a severe downturn. The freight yard had closed in 1982; Sahara Coal Company shut down operations in 1993, and 865 jobs were lost in the county that year.[28] This ended the reign of big coal in Harrisburg, a way of life for residents for over 100 years.[5] The Cairo and Vincennes Railroad/Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago and St. Louis Railway system tracks were taken up in the late 1980s and replaced by the Tunnel Hill State Trail in 1996.[5]

Post-coal economy

[edit]Soon Pioneer history was showcased at the Saline County Area Historical Museum on the city's southern edge. The 3-acre (1.2 ha) site includes the three-story high Old Pauper Home, which was once part of the county's 170-acre (0.69 km2) poor farm, built in 1877. The site also features a variety of cabins, a one-room school house, a small church and other historic buildings that have been acquired, moved to the site and restored.[4]

The Harrisburg-Raleigh Airport is located approximately four miles north of Harrisburg on Highway 34. The Harrisburg-Raleigh Airport Authority operates the airport. The Airport has two runways–32/14 and 6/24. Runway 24 includes a 1,000-foot (300 m) extension, bringing the runway to 5,000 feet (1,500 m) with a GPS-RNAV approach.[29]

Two industrial zones were set up within the township in 1974 by the Saline County Industrial Development Co., one located in Dorrisville, and the other located near the Harrisburg-Raleigh Airport. The one in Dorrisville had the advantage of rail spur prior to the removal of the New York Central tracks. A Tax Increment Finance district was built on the property of the old rail yard north of the city where the Harrisburg Professional Park was built.[30]

The 2000s saw a slight economic boom to the city. The industrial base within the city, while most were not coal-related, gave opportunity to a number of city residents. American Coal and Arclar, the only two coal mines in the county were producing low sulfur coal as an energy resource. Kerr-McGee Coal Corporation's Galatia Complex was purchased by the American Coal Company in 1998.[31] American Coal employed about 580 workers, while Arclar employed 175 persons. Nationwide Glove Factory employed 225 persons, and American Needle was the second-largest non-coal company with 125 workers. Southern Truss and Harrisburg Truss companies employed together 100 employees manufacturing building components.[30] In 2008 construction on the Harrisburg Wal-Mart Supercenter was completed. Wal-Mart will give $21,950 in grants to the Anna Bixby Women's Center, Bridge Medical Clinic, CASA of Saline County, Harrisburg District Library, Harrisburg Police Department, Harvest Deliverance Center Food Pantry, Regional Superintendent of Schools, Saline County Senior Citizens Council and Saline County Sheriff's Department. The building is 184,000 square feet (17,100 m2) and added 150 new jobs to the county. The Supercenter became the second-largest employer in the city, with 340 employees on its payroll.[32] A new strip mall was completed on the south side of town, and Parker Plaza, the oldest shopping center in town was renovated with a new facade to promote commercial growth in the city.[33]

Things slowly took a turn for the worse when former Illinois Governor Rod Blagojevich's decision to move a division of I-DOT to Southern Illinois was overturned by his successor Pat Quinn. Blagojevich's decision outraged lawmakers in Springfield. A lawsuit was filed to stop the move to Harrisburg.[34] Matters were exacerbated when videos of the new home for the IDOT traffic safety division being surrounded by water surfaced on YouTube in late 2007.[35]

The early 2010s saw a series of unfortunate economic events for the city. In December 2010, Harrisburg's AMC, formerly Kerasotes' Cinema 4 theater, closed. This was the first time Harrisburg had been without a cinema since 1920.[36] After release of the 2010 census, in February 2011, the city learned that its population had dropped to a low of 9,017 people, an 8.5 percent decrease.[37] It was the lowest population since the pre-coal boom of 1900. Harrisburg also suffered from numerous scandals involving the school district and police department. In 2011, the Chief Deputy of the Saline County Sheriffs Department was sentenced to prison for sexually abusing a high school student who was working as an intern.[38] The biggest hit was in late February 2012, an EF4 tornado hit Harrisburg during the 2012 Leap Day tornado outbreak. The southern part of the city was heavily damaged, with houses and businesses destroyed, many of which were completely leveled. Eight people were killed and 110 were injured by that tornado.[39][40] In November 2012 a decision was made to close Willow Lake Mine, one of the last remaining mines in Saline County, putting 400 employees out of work.[41]

In 2016, Harrisburg opened a new movie theater. In 2018 Mason Ramsey, a boy from Golconda, went viral after yodeling his rendition of Hank Williams' "Lovesick Blues" in the Harrisburg Walmart. Within a few days videos of his performance collectively garnered over 25 million views and he became a viral sensation and Internet meme.[42]

Harrisburg continues to be the retail hub of Saline County. It holds the nearest shopping centers, restaurants, churches, gas stations, banks, and other commerce within miles.[4] However, industrial jobs are scarce.

Geography

[edit]Harrisburg is located at 37°44′2″N 88°32′45″W / 37.73389°N 88.54583°W (37.733765, −88.545873).[43] According to the 2010 census, Harrisburg has a total area of 6.759 square miles (17.51 km2), of which 6.55 square miles (16.96 km2) (or 96.91%) is land and 0.209 square miles (0.54 km2) (or 3.09%) is water.[44] The square in the center of town, as well as Dorrisville and Gaskins City, stand on top of a series of sandstone bluffs that were once islands rising above natural lowlands, 338 feet (103 m) above sea level, dredged by the middle fork of the Saline River.[45] The Saline River was a navigable river used by early settlers for transportation to and from Salt Works just east of Harrisburg. The Saline flowed towards the Ohio and flooded every spring in events called Freshets. The locals called the island "Crusoe's Island". When the area was drained, homes and businesses were built in the floodplain, and it became prone to serious flooding for years to come.[46] The town square in the center of town is a sandstone bluff 410 feet (125 m) above sea level, one of the first that start the Shawnee Hills to the south. Topographic maps show the bluffs that rise from the Saline River that wraps the northeast part of the city.[47] Harrisburg is located at the ending point of the Laurentide Ice Sheet, which covered about 85 percent of Illinois. The edge of Illinoian ice sheet(s) lay further south than the southernmost extent, i.e. Douglas County, Kansas, of any of the Pre-Illinoian ice sheets.[48]

Gateway to the Shawnee National Forest

[edit]

More than 270,000 acres (1,100 km2) of Shawnee National Forest lie to the south of Harrisburg, drawing visitors annually to the Saline County area and the gateway community. The Shawnee National Forest offers much to see and do. The national forest has 1,250 miles (2,010 km) of roadways, some 150 miles (240 km) of streams and frequent waterfalls, numerous ponds and lakes as large as 2,700 acres (11 km2) (some with swimming beaches), 13 campgrounds, many picnicking sites, and seven wilderness areas where trails are designed for hiking and horseback riding.[49]

Plant life is extremely diverse and ranges from sun-loving species to those that grow in dense shade. Tree cover dominates the publicly owned acreage, and is a significant component on privately owned lands. Oak-hickory is the predominant timber type, however, many other commercially important timber species also occupy significant acreages. More than 500 wildlife species can be found in the Forest, including 48 mammals, 237 birds, 52 reptiles, 57 amphibians, and 109 species of fish. There are seven federally listed threatened and endangered species that inhabit the Forest, as well as 33 species which are considered regionally sensitive, and 114 Forest-listed species.[50]

When the Shawnee Purchase Units were first established, temporary headquarters were set up in Room 303, First Trust and Savings Bank Building, Harrisburg, Illinois. This was the only modern office building in the town of Harrisburg suitable for headquarters, and the forest has continued to occupy this building as Supervisor's offices. Expansion of the offices has continued since 1933, until today (June 1938), ten rooms on the third floor, and four rooms on the fourth floor, are leased by the Forest Service. Employees who were here during the early days of the forest tell of the chaos and confusion caused by the small space under lease, the incoming shipments of equipment and supplies, and the constant inflow of new personnel.[51]

Cottage Grove Fault System

[edit]

After the 5.5 Richter Scale magnitude 1968 Illinois earthquake, scientists realized that there was a previously unknown fault under Saline County, just south of Eldorado near Harrisburg. This fault is called the Cottage Grove Fault, a small tear in the Earth's rock running west–east, in the Southern Illinois Basin. The fault is connected to the north–south trending Wabash Valley Fault System at its eastern end.[52] Seismographic mapping completed by geologists reveal that monoclines, anticlines, and synclines are present within the region; these signs suggest deformation during the Paleozoic era coincident to strike-slip faulting nearby.[53]

A focal mechanism solution of the earthquake confirmed two nodal planes both striking north–south and dipping approximately 45 degrees to the east and to the west. This faulting suggests dip-slip reverse motion, and to a horizontal east–west axis of confining stress.[54] The rupture also occurred partially on the New Madrid Fault, responsible for the great New Madrid earthquakes in 1812, consisting of the most powerful earthquakes to hit the contiguous United States.[55]

Cityscape

[edit]

During the early 20th century, urbanization of the city due to the geographical feature of "Cruesoe's Island" and surrounding coal mining property created a density not seen in many cities of its size. The city at the time with a population nearing 10,000 was forced to tightly cram homes and businesses upon the sandstone outcropping less than a square mile in diameter leading many to build their buildings with multiple stories around the town square. The Saline County courthouse and square have gone through many transformations within the past 100 years. In the 19th century, the town had dirt streets with a large Greek Revival courthouse with Doric columns built by Swiss-born, Evansville, Indiana Architect J. K. Frick & Co in 1861. The courthouse was replaced in 1906 with a larger building designed by then well-known architect John W. Gaddis of Vincennes, Indiana. The structure was an identical model to the Perry County Courthouse at Perryville, Missouri, both built the same year. A smaller version of the central clock tower of the courthouse, including the original clock, manufactured by the Howard Clock Company, of Boston Massachusetts in 1904 was recreated in 1996, and placed in a small lot behind the Clearwave Building's parking lot. The Howard clock company was notable for manufacturing large clocks in such buildings as the Wrigley Building in Chicago, and the Ferry Building in San Francisco, California. The town square was completely surrounded by brick streets in 1906.[19] Harrisburg had 25 miles (40 km) of brick streets,[10] but now only a few blocks are left.[4]

Harrisburg has not yet begun a National Trust for Historic Preservation, Main Street historical preservation program. Saline County is within a recognized historical district, the "Ohio River Route Where Illinois Began". Two buildings in Harrisburg are currently listed on the National Register of Historic Places, those being the City Hall and the Saline County Poor Farm.[56]

The square itself held an array of coal mining offices, privately owned business, grocery and department stores, pharmacies and bars. During the closing of the coal mining era, most of the businesses left the square and moved to the main drag of Rt. 45, constructed in 1926. The courthouse built by John W. Gaddis was replaced with a modern, more efficient building in 1967 after the older building was condemned.[19] Over the years, the architecture that graced Harrisburg square has slowly turned to rotting older structures mixed in with a hodge-podge of newer updated buildings. Currently there are a few privately owned downtown renovation projects in progress on and around the square.[19]

The Harrisburg Mitchell-Carnegie Library, located on Church Street south of the square and built with a grant from Andrew Carnegie, was built in 1908 and opened to the public in 1909. The building served the community until 2000 when the library was moved to a new building on north Main Street. During the 1937 flood, the library was used as a makeshift hospital until the water boiler burst. The building now serves as a church.

Harrisburg has three city parks. Memorial Park, Gaskins City Park, and Dorris Heights Park. Memorial Park, on the west end of town, is the largest[4] with the city park pool and a large lagoon snaking through the center,[57] founded in 1935.[58]

The Sunset Lawn Cemetery is the largest in the county, founded in 1880, connected to the west edge of the city. The cemetery contains ornate tombstones and crypts, within which are the remains of most of the city's original founders and prominent residents. Sunset Lawn contained the 90-year-old Sunset Mausoleum. The crypt had marble floors, with 75 persons buried inside. The structure was condemned in 2008 and there were plans of removal of the bodies and reburial within the cemetery, but due to problems finding many of the family members, has not came to fruition.[59]

In May 2010, on 301 N. Granger Street, the 1895 home of city bricklayer and early proprietor Robert King was set to be demolished. The homeowners donated it to Saline County Habitat for Humanity last year hoping that the organization might be able to restore it. The home was considered "unrestorable".[60] In 2012, Harrisburg High School was placed on the Landmark Illinois endangered buildings list. Two seniors at Harrisburg High School were preparing a nomination of the building for listing in the National Register of Historic Places, and they helped to distribute a petition through social media to help save the school.[61]

Harrisburg neighborhoods

[edit]

Harrisburg is split up into several small neighborhoods that were annexed into the city limits over time, from north to south.[8]

- Dorris Heights – A subdivision established in 1923 on land owned by W.S. and Bertha Dorris. Annexed in 1979. Sits to the direct north of Harrisburg with the Dorris Heights Street being the main road through the area. The Saline County Fair Grounds sits to between Dorris Heights St. and the Levee to the north. Small Street heads east from Dorris Heights towards the Arrow Head Point shopping center.[62]

- Buena Vista – Situated to the south and north of Route 13 (Poplar Street), and west of the main village. It holds the newer town water tower and several homes. It is bordered by Liberty to the south.[8]

- Wilmoth Addition – Is an area of prominently African American residents north of Old Harrisburg, and just south of Dorris Heights. A good portion of the Wilmoth Addition was slowly abandoned and torn down when the Rt. 13 bypass was built in 2008.[8]

- Old Harrisburg Village – The streets that surround the town square. It includes everything on Main street north and south, and Poplar street from the levee to the east and the town park to the west. It also includes the High School, the old Junior High, West and East Side schools, the Courthouse, the town park and cemetery to the west, and the main shopping strip on Route 45. This part of the city is the oldest, and is recognized mainly by the densely packed gilded age houses and structures lined on narrow brick streets. Most of this area is located on "Crusoe's Island", and was built during a pre-automobile-centric Harrisburg.[8]

- Gaskins City – Includes a small village annexed in 1905, named for the Gaskins family of Harrisburg, prominent business owners and coal entrepreneurs of the Egyptian Coal Company, later sold to O'Gara.[63] Gaskins City is a series of several blocks that exists to the east of the Harrisburg Levee and Route 45. Sloan Street crosses Route 45, runs straight into the center of Gaskins City and terminates at the Harrisburg Medical Center. It contains Gaskins City Baptist Church, Shawnee Hills Country Club, and is an upper-class neighborhood. It used to have its own school at one time.[8] A large part of Gaskins City was obliterated by the 2012 EF4 Tornado. Part of Harrisburg Medical Center was also heavily damaged.

- Garden Heights – Slightly south of Gaskins City. Connects it with Route 34 and Pankyville.[62]

- Dorrisville – Straight south of Harrisburg, and established in 1905 with a post office, and annexed by the city in 1923. Dorrisville holds the Dorrisville Baptist Church, the Saline County Area Historical Museum, and "Pauper Farm Crossing", which is on the crossroads of Feazel Street and Route 45. Most people recognize Dorrisville as the first 5–6 blocks north, west, and east of the Feazel Street and Barnett Street 4-way stop.[8] A large part of Dorrisville along the Barnett Street corridor and south of Main Street was destroyed in the tornado. Many houses were destroyed or had lost their roofs.

- Liberty – Was a smaller rural community to the far southwest of Harrisburg along Liberty Road. It included Liberty Church and cemetery. In 1873, designer of the Cairo and Vincennes Railroad, Green Berry Raum of Harrisburg, opened a slope mine on the south side of the rails near Liberty. It became the first in the county to ship coal by rail-car. The mine was called Ledford Slope, and the spot was called Liberty Crossing. Liberty is bordered by the old mining community of Ledford 3 miles (4.8 km) south of Harrisburg, Dorrisville to the west, and Buena Vista to the north. Liberty holds the new Junior High building.[8]

- Ledford – Ledford had been a complete town unto itself. It was the home ground of Charles Birger, and had several stores, its own school system, and a post office. Ledford was a coal mining community set up by mostly Hungarians during the 19th century. It holds a large cemetery, an historic Hungarian cemetery, and the Ledford Baptist Church. Ledford is spread across a 4-mile (6.4 km) span of land along Route 45 between Carrier Mills and Harrisburg, with several roads branching off to the left and right of the highway. It is all considered "Ledford".[8]

Climate

[edit]Harrisburg has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification Cfa), bordering on a humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dfa) with neither large mountains nor large bodies of water to moderate its temperature.[65] Both cold Arctic air and hot, humid tropical air from the Gulf of Mexico affect the region. The city has four distinct seasons. The highest average temperature is in July at 78.7 °F (25.9 °C), while the lowest average temperature is 33.4 °F (0.8 °C) in January.[66] However, summer temperatures can rise over 100 °F (38 °C), and winter temperatures can drop below 0 °F (−18 °C).[67] Average monthly precipitation ranges from a 3.10 inches (79 mm) in September to 5.26 inches (134 mm) in April, with the heaviest occurring during spring.[67][66] Snowfall, which normally occurs from November to April, ranges from 1 to 7 inches (180 mm) per month. The highest recorded temperature was 113 °F (45 °C) on July 13, 1936, and the lowest recorded temperature was on February 2, 1951, at −23 °F (−31 °C).[67]

| Climate data for Harrisburg, Illinois (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1888–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 78 (26) |

80 (27) |

94 (34) |

96 (36) |

100 (38) |

106 (41) |

113 (45) |

111 (44) |

109 (43) |

98 (37) |

87 (31) |

78 (26) |

113 (45) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 42.9 (6.1) |

47.7 (8.7) |

58.1 (14.5) |

69.4 (20.8) |

78.2 (25.7) |

86.0 (30.0) |

89.1 (31.7) |

88.2 (31.2) |

82.4 (28.0) |

71.2 (21.8) |

57.4 (14.1) |

46.8 (8.2) |

68.1 (20.1) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 33.4 (0.8) |

38.0 (3.3) |

47.1 (8.4) |

57.6 (14.2) |

67.3 (19.6) |

75.5 (24.2) |

78.7 (25.9) |

76.9 (24.9) |

69.8 (21.0) |

58.3 (14.6) |

46.8 (8.2) |

37.8 (3.2) |

57.3 (14.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 24.0 (−4.4) |

28.3 (−2.1) |

36.1 (2.3) |

45.7 (7.6) |

56.5 (13.6) |

65.1 (18.4) |

68.4 (20.2) |

65.6 (18.7) |

57.3 (14.1) |

45.4 (7.4) |

36.3 (2.4) |

28.9 (−1.7) |

46.5 (8.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −22 (−30) |

−23 (−31) |

−8 (−22) |

22 (−6) |

28 (−2) |

40 (4) |

45 (7) |

41 (5) |

23 (−5) |

18 (−8) |

−3 (−19) |

−11 (−24) |

−23 (−31) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.79 (96) |

3.13 (80) |

4.90 (124) |

5.26 (134) |

4.31 (109) |

4.92 (125) |

3.49 (89) |

3.58 (91) |

3.10 (79) |

3.76 (96) |

3.97 (101) |

3.38 (86) |

47.59 (1,209) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 7.8 | 6.3 | 8.9 | 10.9 | 9.4 | 7.9 | 6.9 | 6.0 | 6.3 | 6.2 | 7.6 | 8.1 | 92.3 |

| Source: NOAA[67][66] | |||||||||||||

Natural disasters

[edit]Flood risks

[edit]Flooding along the Ohio River, causing back flow of the middle fork of the Saline River has plagued Harrisburg over the years.[68] The city was flooded in 1883–1884 and again in 1913.[19] The most severe came during the Ohio River flood of 1937 when much of the city, except "Crusoes' Island", a downtown orbit that encircled the town square, was underwater. High water had reached 30 miles (48 km) from the river, and the city was flooded in its position among tributary lowlands.[69] 10,000 out of the 16,000 residents were left stranded on the crowded "island" for weeks, while the other 80% of Harrisburg was completely inundated. By the time the flood waters had receded, 4000 were left homeless.[23] Between Gallatin County and Harrisburg, about 25 miles (40 km) of Illinois Route 13 was covered by 8.0 to 14.0 feet (2.4 to 4.3 m) of water; motorboats navigated the entire distance to rescue marooned families.[70] National guard boats were the means of transportation in the city, and several thousand people were transported daily from temporary island to island.[71] According to the Sanborn Map Company, Harrisburg in October 1925 had a population of 15,000, and in a revised version by January 1937 the population had fallen to 13,000.[10] After that, a levee was erected north and east of the city for protection from future floods. The levee became the unofficial northern and eastern border of the town. No businesses or residences exist in the Saline River Middle Fork floodplains.[72] Flooding reoccurred in January 1982 due to drainage problems from the frozen ground, and in 1983, due to 8 inches (200 mm) of rain. The Pankey Branch pumping system, on the east side of town, was built to handle flooding from the Saline River only, and has serious complex watershed technical problems, causing continual water backup within the levee during large rain events. The city rebuilt a new pumping system and requested the Army Corps of Engineers to certify the levee.[68]

Flood of 2008

[edit]In Saline County, a preliminary estimate indicated $16.8 million in damage caused by 11.5 inches (290 mm) of rain on March 18–19, 2008. At least 30 homes and 44 businesses had water over the first floor.[68] Many business owners faced quite a task as they assessed the damage and began cleaning up. Others were able to reopen fairly quickly after suffering only minimal damage or waiting for flood waters to recede so that customers could reach their businesses. Harrisburg officials reported 74 businesses affected by flooding, Businesses along Commercial Street (U.S. Route 45), were hardest hit. Kroger, which had just undergone a major renovation, reportedly had 2 feet (0.6 m) or more of water inside.[73] The Federal Emergency Management Agency denied flood recovery grants and loans to Illinois.[74] Flooding in the city was being called the worst in 71 years.[75]

2012 tornado

[edit]

Spawned by a weather system that had originated in Kansas, an EF-4 tornado slammed into Harrisburg early on the morning of February 29, 2012. The tornado touched down just north of Carrier Mills at 4:51 am, destroyed a church and damaged houses along Town Park Road, and then traveled ENE through the Harrisburg Coal Field just north of Ledford, and then went through Liberty, where it damaged Harrisburg Middle School.[76] The tornado then reached the south-western edge of the city at 4:56 am, specifically Dorrisville, which suffered significant property damage, and then churned eastward to Gaskins City which was nearly leveled; seven people were confirmed dead in that area, most killed in an apartment complex that was crushed by another residence, and 110 were injured overall.[40][77][78] On June 3, another victim died in the hospital from their injuries, raising the death toll to 8.[79] Harrisburg Medical Center was also significantly damaged in Gaskins City.[80] Peak winds were estimated to have been about 180 mph, and the width of the tornado path was 275 yards, traveling 26.5 miles. In Harrisburg, more than 200 houses, and about 25 businesses were destroyed or damaged heavily. At least 10 houses and other buildings were leveled completely, and several structures were displaced from their foundations.[81] Early estimates indicated nearly 40% of the city was damaged or destroyed. The following night, a mandatory curfew was enforced in the effected areas, from 6 p.m. through 6 am.[82] Counting the damage and death toll, it was reported to be the worst storm since the Joplin, Missouri, tornado.[83] Harrisburg Unit 3 schools were closed until March 5, 2012, and later they offered trauma counseling to students after reopening.[84]

The Federal Emergency Management Agency and IEMA[clarification needed] began doing preliminary damage assessments on March 5, 2012, to determine the need for public assistance.[85] The storm damage in Harrisburg dominated national airwaves for several days, with both Anderson Cooper and Diane Sawyer doing special reports.[86][87] Both The New York Times and Chicago Tribune published articles about the resilient history and nature of Harrisburg to rebound from the tornado and floods that have hit the city since its founding in 1889.[88][89]

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1860 | 453 | — | |

| 1870 | 590 | 30.2% | |

| 1880 | 934 | 58.3% | |

| 1890 | 1,723 | 84.5% | |

| 1900 | 2,202 | 27.8% | |

| 1910 | 10,749 | 388.1% | |

| 1920 | 15,054 | 40.1% | |

| 1930 | 15,659 | 4.0% | |

| 1940 | 11,453 | −26.9% | |

| 1950 | 10,999 | −4.0% | |

| 1960 | 9,171 | −16.6% | |

| 1970 | 9,535 | 4.0% | |

| 1980 | 10,410 | 9.2% | |

| 1990 | 9,289 | −10.8% | |

| 2000 | 9,860 | 6.1% | |

| 2010 | 9,017 | −8.5% | |

| 2020 | 8,219 | −8.8% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census | |||

According to the 2010 census,[90] there were 9,017 people living within the city limits. Of the 8,765 persons who identified with one race, 7,983 (88.5%) were white, 589 (6.5%) were black or African-American, 45 (0.5%) American Indian, 74 (0.8%) Asian, 8 (0.1%) Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islanders, and 66 (0.8%) who claimed some other race. The Hispanic population was 209 (2.3%). There were 4,193 total housing units; 3,753 (89.5%) were occupied and 440 (10.5%) vacant.

Media

[edit]The Daily Register, based in Harrisburg, has been providing coverage of news for southeastern Illinois since 1869, and is owned by GateHouse Media.[91] It is the major daily newspaper serving Harrisburg, Saline County, and distributes to Paducah, Kentucky, Cape Girardeau, Missouri, and Mount Vernon, Illinois. The second major newspaper is The Eldorado Daily Journal, based in Eldorado[92] and operated by GateHouse as a sister newspaper to the Register. Newspapers are also delivered into the city from as far away as Evansville, Chicago, and St. Louis. It is often included in the Illinois–Indiana–Kentucky tri-state area.

Harrisburg has one television station licensed directly to the city; WSIL-TV. Broadcasting on channel 3, it is the ABC affiliate for a wide area of southern Illinois, western Kentucky and southeastern Missouri. The station's studios reside in nearby Carterville.[93] There is one major AM broadcasting station in Harrisburg, WEBQ 1240 (also on 93.7 FM), now a country music station that has broadcast news and music to the region since the 1930s, its FM sister station (WEBQ-FM) is a St. Louis Cardinals affiliate and airs an adult standards format. WOOZ 99.9 FM Z100, operating a country format, is also licensed to the city, with studios in nearby Carterville.

Government, healthcare, and education

[edit]Harrisburg is the county seat of Saline County with a mayor and council form of government. The city has four main council members. The city has a Police Department that shares a building with the Sheriff's department with 13 sworn officers and a civilian secretary. The City of Harrisburg Fire Department has 1 Chief 9 full-time union firefighters and 15 paid per call members. All fulltime firefighters are trained Emergency Medical Technicians running a BLS Ambulance. Working out of a central station built in 1991 It houses three engines, a 75ft ladder truck, a heavy rescue, a 4×4 brush truck, a 3000 gallon tanker , 2 side by sides, and 2 boats.

The City of Harrisburg operates its own water distribution system. It has a storage capacity of 6,000,000 US gallons (23 million litres) in elevated tanks. The water processing plant has a capacity of 4,000,000 per day, while average daily consumption is about 2,500,000 gallons. The city's water treatment plant has a design capacity of 3,125,000 gallons per day. Its average load is 1,200,000 US gallons (4.5 million litres) per day.[30]

Harrisburg Hospital was at one time located in a four-story complex one block from the town square,[19] but in the 1990s moved to Harrisburg Medical Center where 71 beds[94] and 34 physicians are on staff. It also has an 18-bed psychiatric area. In 1995, the hospital completed a multimillion-dollar expansion and renovation program. There are 25 nursing homes in the Harrisburg and southeastern Illinois area. Three are located within the city. Harrisburg also has several clinics, and specialized physicians have offices within the city.[30]

Harrisburg Community Unit School District 3 serves the city's student population with two K-6 elementary schools, a junior high school, and a senior high school. More than 2,300 students are enrolled in the district's schools. More than 1,300 students attend East Side and West Side Elementary schools. Malan Junior High was the main middle school for the city until 2005 when the new middle school was built in Liberty, which has 300 students enrolled. Harrisburg High School has more than 600 students enrolled. The city has seven preschools and daycare centers.[30] Harrisburg once had several schools within the township before the different neighborhoods were annexed, all are now closed down, a few are, Horace Mann, McKinley School, Bayliss School, Phillips School, and Ledford school.[19]

Higher education

[edit]Southeastern Illinois College is a two-year junior college that sits on a 148-acre (60 ha) campus east of the city limits. SIC enrolls more than 2,000 students each semester in college transfer and career education programs. SIC was founded in 1960. Other nearby local colleges and universities are Southern Illinois University campus at Carbondale; John A. Logan College, at Carterville; Rend Lake College, at Ina; Eastern Illinois University, at Charleston; Shawnee Community College at Ullin; and the University of Evansville, at Evansville, Indiana.[30]

Transportation

[edit]Rides Mass Transit District provides fixed-route and demand-response transit service in Harrisburg and the surrounding region. The Bulldog Route is the fixed-route bus service that operates within Harrisburg Monday-Saturday.[95]

Popular culture

[edit]- The Good Wife – Season 3, Episode 21 – "The Penalty Box". Character Judge Murphy Wicks, played by actor Stephen Root, lived in Harrisburg, the Gateway to the Shawnee National Forest.[96]

Notable people

[edit]- William Badders, US Navy sailor, Medal of Honor recipient

- Charlie Birger, notorious gangster[97]

- John E. Bradley, state representative[98]

- Danny Fife, MLB pitcher for the Minnesota Twins

- James D. Fowler. state representative[99]

- Virginia Gregg, actress, born in Harrisburg (1916), known as the voice of Norman Bates' mother in Psycho[100]

- Chuck Hunsinger, running back for the Chicago Bears and the Montreal Alouettes; known for fumbling a ball in the 42nd Grey Cup[101]

- John H. Pickering, founding partner of the law firm Wilmer, Cutler & Pickering[102]

- Mason Ramsey, Walmart Yodeling Kid

- General Green Berry Raum, Civil War general, and president of the Cairo and Vincennes Railroad

- John Romonosky, 1950s baseball player, St. Louis Cardinals and Washington Senators[103]

- Dale Swann, character actor born in the Harrisburg[104]

- H. B. Tanner, state representative and businessman.[105]

- Oral P. Tuttle, Illinois, state senator and lawyer[106]

- Henry Turner, physician who first described Turner syndrome[107]

- Stanley B. Weaver. Illinois state legislator and funeral director, was born in Harrisburg.[108]

See also

[edit]- Coal-mining region

- History of coal mining in the United States

- List of coalfields

- Mill town

- Rust Belt

References

[edit]- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 15, 2022.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Population of Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2007 (CBSA-EST2007-01)". 2007 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. March 27, 2008. Archived from the original (CSV) on July 9, 2010. Retrieved July 3, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Community Profile Presents, Harrisburg". Harrisburg Illinois Library. Retrieved April 6, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Schwieterman, Joseph P. (2001). When the Railroad Leaves Town: American Communities in the Age of Rail Line Abandonment, Eastern United States. Kirksville, Missouri: Truman State University Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-943549-97-2.

- ^ Carolyn Stewart, ACSD. "Decennial US Census". Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ^ a b Mardos, Pam (2006). The History of Southern Illinois. unknown.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l A History of Saline County and a Brief History of Harrisburg, Illinois (PDF). Illinois State Historical Society. 1934. p. 25.

- ^ a b c Hitchens, Harold L (1947). Illinois, a Descriptive and Historical Guide. US History Publishers. p. 430. ISBN 1-60354-012-1.

- ^ a b c d e "Digital Sanborn Maps – Splash Page". Harrisburg Illinois Library. Retrieved April 17, 2009.

- ^ Mardos, Pam (2006). The History of Southern Illinois. unknown. p. 1696.

- ^ A History of Saline County and a Brief History of Harrisburg, Illinois. Illinois State Historical Society. 1934. p. 62.

- ^ a b c d e Bill Nunes (2008). Southern Illinois:Amazing Stories From the Past (1st ed.). Corly Printing Of Earth City. ISBN 978-0-9787994-1-0.

- ^ "BIG NEW COAL COMPANY" (Text). The New York Times. July 22, 1905. Retrieved April 8, 2009.

- ^ Mardos, Pam (2006). The History of Southern Illinois. unknown. pp. 1224–1225.

- ^ a b DeNeal, Gary, interview (2003). "The Legend of Charlie Birger". WSIU-TV.

- ^ a b c Hilton, George (2000). The Electric Interurban Railways in America. Stanford University Press. p. 352. ISBN 0-8047-4014-3.

- ^ Standard corporation service, daily revised. Standard Statistics Company. 1917. p. 87.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Daily Register (2003). Commemorating 150 Years of History in Harrisburg, Illinois (1st ed.). Daily Register.

- ^ "MapTool 2". Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ^ Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990. United States Census Bureau, March 27, 1995.

- ^ "75th anniversary of Eleanor Roosevelt visit was Thursday". The Daily Register. Harrisburg, Illinois. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ^ a b The Pittsburgh Press, page 50. United Press, January 29, 1937.

- ^ Chicago Daily Tribune, page 4. United Press, May 9, 1938.

- ^ a b "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov – Publications – U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- ^ "Judge George N. Leighton – Chicago Criminal Lawyers, Illinois Appellate Law, Chicago law firms, illinois appellate lawyers, george leighton". Web.archive.org. Archived from the original on May 15, 2005. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b Kennedy, John F. (August 3, 1960). "Remarks of Senator John F. Kennedy, Harrisburg, IL". John F. Kennedy Library. Retrieved April 17, 2009.

- ^ "Coal is a dirty word". Harrisburg Illinois Library. Retrieved April 8, 2009.

- ^ Homan, John D. (October 21, 2006). "Harrisburg-Raleigh Airport extends runway". The Southern. Retrieved April 8, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f "Harrisburg, Illinois". Community Profile Network. Retrieved April 8, 2009.

- ^ Muir, Jim (January 4, 2006). "Harrisburg-Raleigh Airport extends runway". The Southern. Retrieved April 18, 2009.

- ^ "Rollie Moore Drive Dedicated". Daily Register. October 28, 2008. Retrieved April 18, 2009.

- ^ "Commercial Growth in Harrisburg". WSIL TV. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved April 8, 2009.

- ^ "No IDOT in Harrisburg". WSIL-TV. March 19, 2008. Archived from the original (Text) on July 16, 2011. Retrieved April 6, 2009.

- ^ "Under Controversy Or Under Water". WSIL-TV. August 1, 2007. Archived from the original (Text) on July 16, 2011. Retrieved April 6, 2009.

- ^ Brian DeNeal. "Harrisburg's theater boarded up". The Daily Register. Harrisburg, Illinois. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ^ Emily Finnegan (July 18, 2011), WSIL TV • Census Finds Mixed Results in Southern Illinois, archived from the original on July 18, 2011

- ^ Wells, Len. "Former chief deputy Todd Fort sentenced to prison in intern sex case". Retrieved August 24, 2015.

- ^ "13 killed as tornadoes rake Midwest states". NBC News. February 29, 2012. Archived from the original on February 29, 2012. Retrieved February 29, 2012.

- ^ a b Brian DeNeal. "Seventh person dies from Harrisburg tornado". The Daily Register. Harrisburg, Illinois. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ^ Hibbs, Jason (November 27, 2012). "Mine closed for good, 400 jobs lost". WPSD TV. Saline County, Illinois. Archived from the original on November 30, 2012.

- ^ "Yodeling 'Walmart Boy' from Illinois, Captures Hearts Online". April 4, 2018.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "G001 – Geographic Identifiers – 2010 Census Summary File 1". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved December 27, 2015.

- ^ Geological Survey of Illinois. State journal steam Press. 1875. pp. 207–.

- ^ Transactions of the Illinois State Academy of Science. University of Michigan. 1937. p. 206.

- ^ "Harrisburg USGS Harrisburg Quad, Illinois, Topographic Map". Trails.com. Demand Media, Inc. Retrieved April 8, 2009.

- ^ Stiff, B. J., and A.K. Hansel, 2004, Quaternary glaciations in Illinois. in Ehlers, J., and P.L. Gibbard, eds., pp. 71–82, Quaternary Glaciations: Extent and Chronology 2: Part II North America, Elsevier, Amsterdam. ISBN 0-444-51462-7

- ^ Selbert, Pamela (January 1, 1993). "Balancing act on the Shawnee". American Forests. Archived from the original on April 30, 2009. Retrieved April 8, 2009.

- ^ "Shawnee National Forest". US Forest Service. Retrieved April 8, 2009.

- ^ "The Creation of the Shawnee National Forest 1930–1938". US Forest Service. March 12, 2004. Retrieved April 8, 2009.

- ^ Bristol, Hubert M.; Treworgy, Janis D. (1979). "The Wabash Valley fault System in Southeastern Illinois" (PDF). Circular 509. Urbana, Illinois: Illinois Institute of Natural Resources. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 16, 2010. Retrieved June 11, 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Seismic Reflection Investigation of the Cottage Grove Fault System, Southern Illinois Basin". Geological Society of America. April 4, 2002. Archived from the original on December 4, 2008. Retrieved November 25, 2008.

- ^ Stauder, William; Nuttli, Otto W. (June 1970). "Seismic studies: South central Illinois earthquake of November 9, 1968". Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. 60 (2): 973–981. Bibcode:1970BuSSA..60..973S. doi:10.1785/BSSA0600030973. S2CID 130306348. Archived from the original on July 24, 2011. Retrieved November 9, 2008.

- ^ Staff (November 9, 1968). "Quake Damage Minor; Felt Over Wide Area in Midwest and East". St. Louis Post Dispatch. Archived from the original on October 6, 2008. Retrieved November 9, 2008.

- ^ "Illinois – Saline County". National Register of Historic Places. Retrieved April 8, 2009.

- ^ "Harrisburg Township Park District". Harrisburg Illinois Library. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

- ^ "Oldest Parks celebrated". Harrisburg Illinois Library. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

- ^ "City of Harrisburg Gets Help for Mausoleum". WSIL TV. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved May 7, 2009.

- ^ Daily Register Newspaper, April 15, 2010, Brian DeNeal

- ^ "Landmarks Illinois Ten Most 2012". Archived from the original on November 3, 2014. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ^ a b A History of Saline County and a Brief History of Harrisburg, Illinois. Illinois State Historical Society. 1934. p. 88.

- ^ "History of Southern Illinois ~ Biography of John T. Gaskins". Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ^ "FCC Registered Cell Phone and Antenna Towers in Harrisburg, Illinois". Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ^ Peel, M. C.; Finlayson B. L. & McMahon, T. A. (2007). "Updated world map of the Köppen−Geiger climate classification" (PDF). Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 11 (5): 1633–1644. Bibcode:2007HESS...11.1633P. doi:10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007. ISSN 1027-5606.

- ^ a b c "Station: Harrisburg, IL". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 26, 2021.

- ^ a b c d "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 26, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Flooding Continuing Problem, Jim Brown" (Text). Harrisburg Daily Register. March 17, 2009. Retrieved April 6, 2009.

- ^ Davis, Norman (1938). The Ohio-Mississippi valley flood disaster of 1937: Report of relief operations of the American Red cross. American Red Cross. p. 79.

- ^ Hitchens, Harold (1947). Illinois, a Descriptive and Historical Guide. US History Publishers. p. 436.

- ^ Walton, Clyde (1970). An Illinois reader. Northern Illinois University Press. p. 431.

- ^ Rhodes, Lester (1939). Flood Protection Project, Harrisburg, Illinois. War Dept., U.S. Engineer Office. p. 123.

- ^ "After the Flood". WSIL-TV. March 24, 2008. Archived from the original (Text) on March 28, 2008. Retrieved April 6, 2009.

- ^ "Southern Illinois Denied Help From FEMA". WSIL-TV. September 7, 2008. Archived from the original (Text) on October 6, 2008. Retrieved April 6, 2009.

- ^ "Grocery Store Woes". WSIL-TV. March 24, 2008. Archived from the original (Text) on October 6, 2008. Retrieved April 6, 2009.

- ^ "Harrisburg Middle School suffered tornado damage – ksdk.com". ksdk.com. Archived from the original on January 4, 2013. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ^ Christy Hendricks (February 29, 2012). "5 confirmed tornadoes in the Heartland – KFVS12 News & Weather Cape Girardeau, Carbondale, Poplar Bluff". Archived from the original on June 14, 2012. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ^ "Storm toll in Illinois lowered to 6 dead from 10 – governor's office". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved February 29, 2012.

- ^ "Harrisburg tornado death total now stands at 8". Harrisburg, Illinois. WGCL-TV. June 1, 2012. Archived from the original on April 25, 2016. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- ^ "Tornado damages Illinois hospital". Archived from the original on September 13, 2014. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ^ "National Weather Service updates tornado statistics – News – The Daily Register – Harrisburg, Illinois". The Daily Register. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ^ Scott Fitzgerald (March 1, 2012). "'We will rebuild': Harrisburg mayor vows town will become stronger". Harrisburg, Illinois. The Southern Illinoisan. Archived from the original on April 25, 2016. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- ^ "Harrisburg, Illinois tornado one of the worst tornadoes since Joplin disaster". February 29, 2012. Archived from the original on March 4, 2012. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ^ "Unit No. 3 schools provide trauma counseling to students – News – The Daily Register – Harrisburg, Illinois". The Daily Register. Archived from the original on April 14, 2012. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ^ "FEMA, IEMA officials begin conducting damage assessments – News – The Daily Register – Harrisburg, Illinois – Harrisburg, Illinois". The Daily Register. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ^ TV.com. "ABC World News with Diane Sawyer – Season 201202, Episode 02.29.12: Harrisburg, Illinois, Devastated by Tornadoes – TV.com". TV.com. Archived from the original on September 13, 2014. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ^ "Tonight, tragic stories of losing loved ones and also incredible tales of..." Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ^ Davey, Monica (March 1, 2012). "Southern Illinois Town Is All Too Versed in Taking a Hit". The New York Times.

- ^ "Topic Galleries". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Daily Register". GateHouse Media, Inc. 2009. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

- ^ "Echo Media Harrisburg Register & Eldorado Journal". ECHO MEDIA. 2005. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

- ^ "WSIL-TV". WSIL. 2009. Archived from the original on March 21, 2009. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

- ^ "About Us : Harrisburg Medical Center". Retrieved April 28, 2019.

- ^ "RMTD Saline County". Retrieved October 4, 2023.

- ^ ""The Good Wife" The Penalty Box". IMDb.

- ^ The Legend of Charlie Birger – WSIU-TV documentary (2003)

- ^ Illinois General Assembly-John E. Bradley

- ^ 'Illinois Blue Book 2001–2002,' Biographical Sketch of Jim Fowler, pg. 130

- ^ "Virginia Gregg Biography". Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ^ Toronto Star, Wednesday November 27, 1968, page 14, Jim Kernaghan column.

- ^ New York Times, March 22, 2005, "John H. Pickering, 89, a Founder of a Leading U.S. Law Firm, Is Dead"

- ^ "John Romonosky Statistics and History". Retrieved April 6, 2009.

- ^ Bassett, Kathie (April 14, 2009). "Charactor actor Dale Swann dies". The Telegraph (Alton). Archived from the original on April 18, 2009. Retrieved April 18, 2009.

- ^ 'Illinois Blue Book 1965–1966,' Biographical Sketch of H. B. Tanner, pg. 296–297

- ^ 'Illinois Blue Book 1937–1938,' Biographical Sketch of Oral P. Tuttle, pg. 234–235

- ^ A Tribute to Henry H. Turner, M.D. (1892–1970): A Pioneer Endocrinologist. The Endocrinologist 14(4) 179–184, July–August 2004, G. Bradley Schaefer, MD, and Harris D. Riley Jr., MD

- ^ 'Former Urbana mayor and longtime legislator dies,' The News-Gazette, J. Philip Bloomer, November 12, 2003

External links

[edit]- Saline County Chamber of Commerce

- Southeastern Illinois Regional Planning and Development Council

- Harrisburg Official Website

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.