Adolf Dassler

Adolf Dassler | |

|---|---|

Dassler at age 15, c. 1915 | |

| Born | 3 November 1900 |

| Died | 6 September 1978 (aged 77) Herzogenaurach, West Germany |

| Occupation | Founder of Adidas |

| Political party | Nazi Party (1933–1945) |

| Spouse(s) | Käthe (née Martz) (17 July 1917 – 31 December 1984) |

| Parent(s) | Christoph Dassler (father) Pauline Dassler (mother) |

| Relatives | Fritz Dassler (brother) Marie (sister) Rudolf Dassler (brother) Horst Dassler (son) Armin Dassler (nephew) |

Adolf "Adi" Dassler (3 November 1900 – 6 September 1978) was a German cobbler, inventor and businessman who founded the German sportswear company Adidas. He was also the younger brother of Rudolf Dassler, founder of Puma. Dassler was an innovator in athletic shoe design and one of the early promoters who obtained endorsements from athletes to drive sales of his products. As a result of his concepts, Adi Dassler built the largest manufacturer of sportswear and equipment. At the time of his death, Adidas had 17 factories and annual sales of one billion marks.[1]

Life

[edit]The Brothers Dassler Shoe Factory 1918–1945

[edit]

Adi supported himself while attempting to start up his business by repairing shoes in town.[2] Facing the realities of post-war Germany where there was no reliable supply for material for production or credit to obtain factory equipment or supplies, he began by scavenging army debris in the war-countryside: Army helmets and bread pouches supplied leather for soles; parachutes could supply silk for slippers.[3]

Dassler became quite adept at modifying available devices to help mechanize production in the absence of electricity. Using belts, for example, he rigged a leather milling machine to a mounted, stationary bicycle powered by the firm's first employee.[2] The business was driven by Adi's vision of specialized sport designs. He produced one of the earliest spiked shoes, with spikes forged by the smithy of the family of his friend Fritz Zehlein.[3] He constantly experimented with various materials, such as shark skin and kangaroo leather, to create strong but lightweight shoes. Years later his widow, Käthe Dassler, said: "Developing shoes was his hobby, not his job. He did it very scientifically."[4]

After the war, Rudolf was determined to become a policeman. But after he completed his training, he joined Adi's firm on 1 July 1923.[5] With the support of the Zehlein smithy producing spikes, Adi was able to register Gebrüder Dassler, Sportschuhfabrik, Herzogenaurach ("Dassler Brothers Sports Shoe Factory, Herzogenaurach") on 1 July 1924, where they were operating in a former washroom that was converted to a small workshop with manual electricity generation.[5][6][7] By 1925, the Dasslers were making leather Fußballschuhe (football boots) with nailed studs and track shoes with hand-forged spikes.[8]

Two factors paved the way for the transformation of the business from a small regional factory, which they moved to in 1927 from their parents' home, to the international shoe distributor it would become. First was the interest showed by former Olympian and then coach of the German Olympic track-and-field team, Josef Waitzer. On learning of the plant and Adi's experiments, Waitzer travelled from Munich to Herzogenaurach to see for himself. A long friendship developed between the two, based on interest in improving athletic performance with improved footwear, and Waitzer became something of a consultant to the company. The relationship proved extremely valuable in giving Adi access to the athletes, both German and foreign, at the 1936 Berlin Olympics.[9][10]

As early as the 1928 Amsterdam games, the Dasslers' footwear was being used in international competitions.[8] Lina Radke, for example, the German middle distance runner who won gold in 1928, wore Dassler track shoes.[7] Likewise, a German gold medal runner wore Dassler shoes at the 1932 Los Angeles games.[11] The second key factor for the shoe firm in the early 1930s was the role sport played in the racial-nationalist philosophy of Hitler. With the rise of the National Socialist German Workers Party, athletic teamwork was prioritized. The Dassler brothers did not fail to see how their economic interest would benefit from politics. All three Dassler brothers joined the Nazi Party on 1 May 1933—three months after Hitler was appointed Chancellor.[12] Rudolf was said to be most ardent believer of the three.[13]

Adi decided that becoming a coach of and supplier to clubs in the Hitler Youth movement was essential to expanded production. He joined in 1935.[14] During his denazification proceedings after the war, Adi pointed out that he had confined himself to coaching and avoided political rallies. He testified that he was involved in clubs with other political affiliations, such as a liberal gymnastic club, Herzogenaurach's conservative KHC football club and a workers' sports club named "The Union".[15] Both Adi and Rudolf were members of the National Socialist Motor Corps, and in their correspondence both used the complimentary closing, "Heil Hitler."[16]

In the early 1930s, Adi Dassler enrolled in the Schuhfachschule (the Footwear Technical College) in Pirmasens. One of the instructors was Franz Martz, a master producer of lasts. Dassler became a frequent house guest of Martz, who allowed Dassler to begin a relationship with his fifteen-year-old daughter, Käthe Martz. On 17 March 1934, the two wed.[17] Unlike Rudolf's wife Friedl (née Strasser), Käthe was somewhat self-assertive and suspicious of the brusque ways of Franconians. She had frequent run-ins with Adi's parents and Rudolf and his wife, all of whom lived in the same house.[18]

Years later, in a letter to Puma's American distributor, Rudolf blamed the rift with his brother entirely on Käthe, claiming that she "tried to interfere in business matters". He claimed that the brothers' relations were "ideal" until 1933.[19] Käthe gave birth to their son Horst in March 1936, their first daughter Inge in June 1938, and their second daughter Karin in 1941.[20] After the war, Brigit was born in May 1946 and Sigrid in 1953.[21][22]

Dassler saw the 1936 Berlin Olympics as the key springboard for international exposure. Although his relation with Waitzer ensured that most German athletes wore Dassler footwear, Dassler had another athlete principally in mind—Jesse Owens, the American track-and-field star. Dassler found his way to meeting Owens and wordlessly offered his shoes to the American star. Owens accepted the gesture and wore the distinctive shoes, with two leather strips on the sides and dark spikes, when he defeated Luz Long in the long jump, shattering his own record in the process, and in his two individual gold-winning performances in track and as a member of America's Gold medal upset of the German relay team.[23]

Dasslers' association with Owens proved crucial to the success of the firm. Not only did it immediately catapult the company into an international player in the sportswear field, spiking sales overall, it quite literally later saved the firm. When American troops discovered that the Dassler factory was where the shoes for Owens' Olympic victories were made, they decided to let the works remain standing, and many of the troops became good customers.[14] Large orders for basketball, baseball and hockey footwear gave the Dasslers "the first boost on the road to becoming a worldwide success story."[11]

Once war began, the Dasslers' ability to profit from Nazi enthusiasm for sport ended as the Reich became a total war machine. The Dassler firm was permitted to operate, but its production was severely curtailed. On 7 August 1940 Adi received notice of his conscription into the Wehrmacht. Although he reported in December to begin training as a radio technician, he was relieved of duty on 28 February 1941 on the ground that his services were essential in Gebrüder Dassler.[24] Rudolf, who had already served four years during the Great War, was drafted in January 1943.[25]

In the early years of the war, the firm was partially converted to a factory for the production of military material. Staff were reduced and supply was hard to come by. It continued to produce Waitzer shoes, although some of its football line became known as "Kampf" and "Blitz." By October 1942, worker shortages became so severe that Adi Dassler requested the use of five Soviet prisoners of war to man his production line.[20]

Wartime conditions exacerbated the simmering dispute between Rudolf and Adi's families. The house that Christoph, Pauline, sons Rudolf and Adi and their wives, and five grandchildren all lived in together seemed stifling, and forced family association at work was further complicated by sister Marie's employment there. Rudolf, angry that his younger brother was determined to be the leader of the Dassler firm, and therefore released from the Wehrmacht, began to assert himself among family members. He used this assumed authority to deny employment to two of Marie's sons, asserting that "there were enough family problems at the company."[26]

The decision devastated his sister, since those not employed in permitted industries were nearly guaranteed to be drafted, as the army's manpower needs increased.[26] Marie's sons were eventually conscripted, and they never returned from the war.[27] Fritz Dassler, who was not on speaking terms with Adi, made a similar decision, laying off a teenaged seamstress who worked for his lederhosen-turned-army-pouch manufacturer, but had worked previously for four years for Adi. Adi managed to make room at the shoe factory to protect her for the rest of the war.[28]

Rudolf's rage boiled over when he was called up again in January 1943 as part of a total mobilization program. He later expressed to the Puma American distributors the belief that he was unfairly repaid for getting his brother "released for the factory" in 1942, and claimed that for his own immediate conscription he "had to thank my brother and his [Nazi] party friends …".[29] Stationed in Tuschin in April 1943, Rudolf wrote to his brother: "I will not hesitate to seek the closure of the factory so that you be forced to take up an occupation that will allow you to play the leader and, as a first-class sportsman, to carry a gun."[30]

Six months later the factory was shut down, but as part of the Reich's Totaler Krieg—Kürzester Krieg (Total War—Shortest War) campaign, part of which involved converting all industry to military production. On leave at the time of the shut down, Rudolf intended to take some of the leather inventory for his own later use. Stunned to find that Adi had already done so, he denounced his brother to the Kreisleitung (the county level Party leaders), according to Käthe, who treated her husband "in the most demeaning manner."[31]

In December 1943 the shoe-making machinery of the Dassler firm was replaced by spot-welding machines. The Army determined that the Dassler plant would make Panzerschreck, a shoulder-fired tube copied after captured American bazookas. Like the American proto-type, the weapon was designed to be relatively light-weight and able to penetrate tank armor. Stationary testing suggested it could penetrate 230 mm (9"), 15–75 mm (½" to 3") deeper than the American bazooka.[32] The Army's contractor was Schriker & Co., located in nearby Vach, which shifted assembly to Herzogenaurach to avoid Allied air raids. Parts were transported by rail to the Dassler plant where they were welded.[11]

The simple design of the weapon allowed the contractor to quickly train former seamstresses to spot weld sights and blast shields onto the pipes provided. The more complicated production of rockets continued in Vach. The weapons were to be distributed to tank-destroying detachments. By March 1945 92,000 Panzerschrecks were in active use at the fronts of the rapidly constricting periphery of German territory. Although the weapon was remarkably effective and easily produced, its availability came too late in the war to save the Reich.[11]

Back in Tuschin, Rudolf continued to make good on his resolve to wrest the plant from his brother. Using contacts at the Luftwaffe he attempted to have the production of Panzerschrecks replaced by government-ordered production of army boots under a patent he personally held. The patent proved defective, and his plan came to nothing.[33] Unable to obtain permission to leave the Polish outpost, Rudolf turned to his own devising. Several weeks before 19 January 1945, the Soviets overran Tuschin (which then reverted to its original name, Tuszyn) and decimated his unit. Rudolf fled to Herzogenaurach, where a doctor provided him a certificate of military incapacity owing to a frozen foot.[34]

The now-defunct unit had been folded into the Schutzstaffel (SS). The sources for what Rudolf did between his desertion from Tuschin and the funeral of Rudolf's and Adi's father on 4 April 1945 is among the disputed records in the American denazification panels. On the day after the funeral he was arrested and taken to the Bärenschanze prison run by the Gestapo in Nürnberg. He remained there until the Allied liberation in early May.[34]

When American troops reached Herzogenaurach, tanks paused before the Dassler factory pondering whether to blow it up. Käthe immediately approached the troops and argued that the plant was simply a sports shoes producer. The troops spared the plant, taking over the family house in the process. Two weeks after the liberation of Herzogenaurach, Rudolf returned. As the American denazification process proceeded, the threat of liability from their Nazi past drove an irreconcilable rift between brothers Rudolf and Adi, each seeking to save himself.[35]

The denazification proceedings and the family rupture 1946

[edit]

On 25 July 1945, about two months after the arrival of U.S. troops, Rudolf was arrested by the American occupation authorities on suspicion of having worked for the Sicherheitsdienst, the secret service of the Reichsführer-SS (commonly known as the SD), which had been engaged in counterespionage and censorship. He was sent to an internment camp in Hammelburg.[36] Rudolf began to prepare a defense in which he asserted that he did not voluntarily help the Reich and did not engage in SS or SD activities. The American investigators soon discovered his early Nazi party membership and proof that he had volunteered for the Wehrmacht in 1941. They even knew that in Tuschin his job was to keep track of "personal and smuggling cases."[37]

Rudolf's key problem was explaining his activities after he had been summoned to Nuremberg in March by the Gestapo. Rudolf maintained that he had been summoned on 13 March for an investigation of his earlier unauthorized departure from Tuschin, and did nothing but report daily to the Gestapo while they investigated him for over two weeks. He claimed that he had escaped on 20 March.[37] Rudolf used written statements of his former superior in Tuschin, who was in the same camp and alleged to be the intelligence chief of the region, and a driver he had encountered after he was arrested by the Gestapo in April, who was incarcerated with Rudolf. Rudolf made much use of the latter's testimony, and averred that he had been sentenced by the Gestapo to Dachau concentration camp.[38]

Rudolf claimed that the driver, who had been ordered to shoot all the prisoners en route, disregarded the order and continued toward Dachau, but was stopped by advancing Allied troops, to whom he released the prisoners, including Rudolf. The American investigator in charge of the case did not credit any of this testimony, which he regarded as mere cover for the unlawful activities of all three men. He noted that both Rudolf's wife and his brother Adi testified that Rudolf had worked for the Gestapo.[38] The investigation continued for nearly a year. During that time it became apparent that it was not possible to hold all the prisoners for a detailed examination of the case. The authorities decided to release all persons not deemed to be a security threat. Rudolf was released on 31 July 1946.[21]

Before Rudolf was released, Adi had to appear before the denazification panel. The result was announced on 13 July 1946: Adi was declared a Belasteter, the second most serious category of Nazi offenders, which included profiteers, and could lead to a sentence of up to 10 years in prison for those convicted.[39][40] The immediate threat was that he would be removed from management of the firm. His early membership in the Nazi Party and the Hitler Youth were not contestable. On appeal, he amassed a portfolio of testimony attesting to his good conduct during the war. Adi's staunchest supporter was Herzogenaurach's mayor, who the Allied forces trusted.[41]

A nearby mayor, who was half-Jewish, testified that Adi warned him of a potential Gestapo arrest, and hid him on his own property. A longtime Communist party member testified that Adi was never involved in political activities. Adi showed that, far from profiting from the forced weapons production, the firm lost 100,000 marks. Despite Adi's evidence, the committee did not acquit him.[41] Instead, they reclassified him as Minderbelasteter (Lesser Offender),[42] a category of lesser culpability resulting in probation of two to three years with various conditions[43] but still requiring that Adi not operate Dassler Shoes.[44] Adi hired counsel to appeal the decision. Rudolf, who had just been released, saw this as his opportunity to wrest control of the business from Adi.[citation needed]

In the course of the appeal proceedings Rudolf Dassler inserted statements that claimed that Adi Dassler had organized the production of weapons himself and for his own profit and that Rudolf would have resisted the change in production if he were present. He claimed that his brother had falsely denounced him and that Adi had made political speeches to employees at the plant. Among other proofs submitted by Adi's counsel was a strong denial of all Rudolf's claims by Käthe.[45] On 11 November 1946 the Spruchkammer Höchstadt sitting in Herzogenaurach changed Adi's status to Mitläufer (follower), relieving him of most of his civil disabilities,[46] but still required some supervision.[47] On 3 February 1947, ownership was returned and he was formally granted permission to resume management of the firm.[42]

Rudolf's belief that Adi had denounced him and his conduct during his brother's appeal made further relations between them impossible. In fact, it irreparably divided the family. Mother Paulina sided with Rudolf and Friedl, who cared for her the rest of her life. Their sister Marie, who never forgave Rudolf for the death of her sons, sided with Adi and Käthe. Rudolf, his wife and two children left the family home and moved across the river, where he took over the second factory of the Dassler firm. In their separation Adi retained the first factory and the family villa. As for the rest of the firm's assets, the two divided them one-by-one.[27] Once the brothers divided their businesses they never spoke again.[48]

Founding Adidas 1946–1947

[edit]After the war, the Dassler firm found itself with some of the same problems that it faced at the beginning. A world war had decimated the German economy and supplies for the shoe factory were hard to come by. In addition, the firm had to convert back from weapons to shoe production. This time, the American occupying authorities were interested in reviving economic activity, so they gave the firm active encouragement. American officers had commandeered the Dassler house for their residence in April 1945, so Adi had close contact with officials who gave him access to unneeded war material for production. Until a source of leather became available, Adi made use of the rubber from fuel tanks and rafts and canvas from tents to make shoes. Adi was able to produce shoes, and save for the months in 1946 while under the classification of Belasteter. He was able to manage the business from July 1946 to February 1947 under the supervision of a trustee, until the business separation from his brother in 1948.[49]

During the negotiations to separate the firm, Rudolf and Adi allowed the employees to determine which resulting firm they would work for. Because Rudolf had mainly concerned himself with sales and administration, most of the sales staff opted to join Rudolf at the Würtzburger Strasse factory. The rest, including almost all the technicians and those involved in product development and production, remained with Adi.[27] Adi ended up with nearly two-thirds of the employees.[48] To partially fill the void left by the departure of the administrative personnel, Käthe and her sister Marianne Martz joined the firm and acted in a variety of capacities.[50]

Meanwhile, Adi was concerned in designing a distinctive look for his shoes, at least partially so that it would be possible to show which athletes used his footwear. He fell upon the idea of coloring the straps used for reinforcement on the sides of the shoes a different color than the shoes themselves. He experimented with different numbers of straps and ultimately decided upon three. The "three stripes" became a distinctive mark of Adidas shoes. In March 1949, Dassler registered the three stripe logo as the company's trademark.[51]

As for the company's name, the plan was to use a contraction of Adi's nickname and last name, much as Rudolf originally contemplated by naming his firm "Ruda" before deciding on "Puma",[27] but "Addas" was rejected on the ground that it was used by a children's shoe manufacturer. In his August 1949 company registration, Adi added a handwritten "i" between Ad- and -das to maintain the contraction (Adi Dassler). As a result, the company became known as Adolf Dassler adidas Schuhfabrik.[48]

Adidas' breakthrough 1948–1978

[edit]Like the Dasslers, Sepp Herberger joined the Nazi Party in 1933.[52][53] In 1936, after Germany's humiliating quarter final defeat by Norway at the Berlin Games, the Nazi sports authorities appointed him to coach the national football team. Herberger began an association with the Dassler firm, having been cultivated by Rudolf Dassler. After the breakup Herberger sided with the Puma firm, until Rudolf once again felt his authority challenged and insulted him. Herberger switched his allegiance to Adidas.[54] The nature of the dispute is unknown. Some thought it involved the payments owed if the German team wore Puma shoes.[55]

In many respects the fit was better with Adi, who was quiet, willing to learn the needs of football players and more innovative than his brother. Herberger's drive to make Germany a dominant force in international football predated the war. He learned of 18 year old Fritz Walter in 1938 and began grooming him for the team. When war came, Herberger was able to keep Walter out of the army. After the war, Herberger was deemed a Mitläufer and the post-war German authorities continued him as the coach of the national team.[52] Adi soon became a regular part of the entourage of the national team, who sat beside Herberger and adjusted players' shoes mid-game.[52]

West Germany, established in May 1949, was not eligible for the 1950 World Cup, the first after the war, and so all preparations were made with a view toward the 1954 matches in Switzerland. By that time Adidas's football boots were considerably lighter than the ones made before the war, based on English designs. At the World Cup Adi had a secret weapon, which he revealed when West Germany made the finals against the overwhelmingly favored Hungarian team, which was undefeated since May 1950 and had defeated West Germany 8–3 in group play.[52]

Despite this defeat, West Germany made the knock-out rounds by twice defeating Turkey handily. The team defeated Yugoslavia and Austria to reach the final, a remarkable achievement, where the hope of many German fans was simply that the team "avoid another humiliating defeat" at the hands of the Hungarians.[52] The day of the final began with light rain, which brightened the prospects of the West German team who called it "Fritz Walter-Wetter", because the team's best player excelled in muddy conditions.[56]

Dassler informed Herberger before the match of his latest innovation—"screw in studs." Unlike the traditional boot which had fixed leather spike studs, Dassler's shoe allowed spikes of various lengths to be affixed depending on the state of the pitch. As the playing field at Wankdorf Stadium drastically deteriorated, Herberger famously announced, "Adi, screw them on."[52]

The longer spikes improved the footing of West German players compared to the Hungarians whose mud-caked boots were also much heavier. The West Germans staged a come from behind upset, winning 3-2, in what became known as the "Miracle in Bern." Herberger publicly praised Dassler as a key contributor to the win. Adidas's fame rose both in West Germany, where the win was considered a key post-war event in restoring German self-esteem[52][56] and abroad, where in the first televised World Cup final viewers were introduced to "the ultimate breakthrough."[57]

Personal life

[edit]Dassler was married to Käthe until his death from heart failure in 1978. They had 5 children. In 1973, their son Horst Dassler founded Arena, a producer of swimming equipment. Käthe Dassler died on 31 December 1984.[58]

Posthumous

[edit]After Adolf Dassler's death, his son Horst and his wife, Käthe, took over the management. Horst died on 9 April 1987.[59]

Adidas was transformed into a private limited company in 1989, but remained family property until its IPO in 1995. The last of the family members who worked for Adidas was Frank Dassler (the grandson of Rudolf), head of the legal department since 2004, who resigned in January 2018.[60]

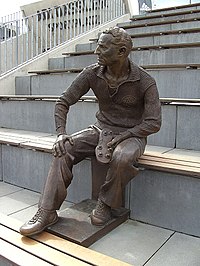

In 2006 a sculpture of Dassler was unveiled in the Adi Dassler Stadium in Herzogenaurach. It was created by the artist Josef Tabachnyk.[61]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Gestorben: Adolf ('Adi') Dassler". Der Spiegel. 11 September 1978. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ^ a b "1920–1922: Inventive Spirit and First Shoe Production Chronicle and Biography of Adi & Käthe Dassler". Adi & Käthe Dassler Memorial Foundation. 2018. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ^ a b Smit 2008, p. 5.

- ^ Tagliabue, John (15 February 1981). "Adidas, Puma: The Bavarian Shoemakers". The New York Times. p. F8. Archived from the original on 25 July 2018. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ^ a b "1923–1927: Founding of the Dassler Brothers' Sport Shoe Factory Chronicle and Biography of Adi & Käthe Dassler". Adi & Käthe Dassler Memorial Foundation. 2018. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ^ Smit 2008, pp. 5–6.

- ^ a b "History". Adidas Group. Archived from the original on 17 August 2018. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ^ a b "Adolph (Adi) and Rudolf (Rudi) Dassler". Fashion Model Directory. Archived from the original on 25 July 2018. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ^ Smit 2008, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Coles, Jason (2016). Golden Kicks: The Shoes that Changed Sport. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 22–24.

- ^ a b c d Kuhn, Robert; Thiel, Thomas (4 March 2009). "The Prehistory of Adidas and Puma: Shoes and Nazi Bazookas". Spiegel Online. Archived from the original on 11 July 2018. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ^ Smit 2008, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Kirschbaum, Erik (8 November 2005). "How Adidas and Puma were born". Rediff.com. Reuters. Archived from the original on 17 January 2008. Retrieved 14 July 2008.

- ^ a b Coles 2016, p. 24.

- ^ Smit 2008, p. 29.

- ^ Smit 2008, p. 14.

- ^ Smit 2008, p. 12.

- ^ Smit 2008, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Smit 2008, pp. 13–14, 347.

- ^ a b Smit 2008, p. 16.

- ^ a b Smit 2008, p. 27.

- ^ Smit 2008, p. 39.

- ^ Smit 2008, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Smit 2008, p. 15.

- ^ Smit 2008, p. 18.

- ^ a b Smit 2008, pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b c d Smit 2008, p. 31.

- ^ Smit 2008, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Smit 2008, pp. 18–19, 347.

- ^ Smit 2008, p. 19.

- ^ Smit 2008, p. 19–20.

- ^ "Panzerfaust & Panzerschreck". Jaeger Platoon. 18 March 2018. Archived from the original on 24 July 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ^ Smit 2008, p. 20.

- ^ a b Smit 2008, pp. 20–21, 347–48.

- ^ Smit 2008, pp. 21–23.

- ^ Smit 2008, pp. 23–24.

- ^ a b Smit 2008, pp. 21, 25–26.

- ^ a b Smit 2008, pp. 23, 26.

- ^ Junker, Detlef; Gassert, Philipp; Mausbach, Wilfried; Morris, David B. (2004). The United States and Germany in the Era of the Cold War, 1945-1990: A Handbook. Vol. 1. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 67–68.

- ^ Plischke, Elmer (October 1947). "Denazification Law and Procedure". The American Journal of International Law. 41 (4): 807–827. doi:10.2307/2193091. JSTOR 2193091. S2CID 147316001.

- ^ a b Smit 2008, pp. 28–29.

- ^ a b "1945–1947: The Postwar Years". Chronicle and Biography of Adi & Käthe Dassler. Adi & Käthe Dassler Memorial Foundation. 2018. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2018. This source contains a copy of the verdict.

- ^ Junker et al. 2004, p. 68.

- ^ Plischke 1947, pp. 824–25.

- ^ Smit 2008, p. 30.

- ^ Smit 2008, p. 348.

- ^ Plischke 1947, p. 825.

- ^ a b c "1948–1949: Separation of the Brothers and Birth of the Three Stripes". Chronicle and Biography of Adi & Käthe Dassler. Adi & Käthe Dassler Memorial Foundation. 2018. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ^ "1945–1947: The Postwar Years". Chronicle and Biography of Adi & Käthe Dassler. Adi & Käthe Dassler Memorial Foundation. 2018. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ^ Smit 2008, p. 32.

- ^ Smit 2008, pp. 31–33.

- ^ a b c d e f g Smit, Barbara (24 July 2004). "Miracle Men". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 4 August 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ^ "German Federation Admits to Nazi Past". The New York Times. 20 September 2005. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ^ Smit 2008, p. 34.

- ^ Tousif, Muhammad Mustafa (August 17, 2016). "Adidas vs Puma: Key Battles (Part 2)". Bundesliga Fanatic. Archived from the original on August 21, 2018. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

- ^ a b Wessell, Markus (4 September 2009). "Hoch gepokert und gewonnen". Arbeitsgemeinschaft der öffentlich-rechtlichen Rundfunkanstalten der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ "1954–1959: Removable Cleats and the Football World Championship 1954". Chronicle and Biography of Adi & Käthe Dassler. Adi & Käthe Dassler Memorial Foundation. 2018. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ "Käthe Dassler, Co-Founder Of Adidas, Dies in Germany". The New York Times. 2 January 1985. p. B8. Archived from the original on 10 July 2018. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ^ "Horst Dassler Is Dead at 51; Led Adidas Sporting Goods". The New York Times. 11 April 1987. p. A32. Archived from the original on 10 July 2018. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ^ "Dassler-Spross verlässt Sportartikelkonzern". Spiegel Online. 2 February 2018. Archived from the original on 7 April 2018. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2013. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

Sources

[edit]- Smit, Barbara (2008). Sneaker Wars: The Enemy Brothers who Founded Adidas and Puma and the Family Feud that Forever Changed the Business of Sport. New York: CCCO/HarperCollins Publishers. p. 4. ISBN 9780061246579.

- 1900 births

- 1978 deaths

- Dassler family

- People from Herzogenaurach

- German company founders

- 20th-century German businesspeople

- 20th-century German inventors

- Shoe designers

- German fashion designers

- German military personnel of World War II

- Nazi Party members

- People from the Kingdom of Bavaria

- Adidas people

- Officers Crosses of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

- German military personnel of World War I

- National Socialist Motor Corps members