My Own Prison

| My Own Prison | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | April 14, 1997 (Blue Collar release) August 26, 1997 (Wind-up release) | |||

| Studio |

| |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 51:56 (Blue Collar release) 49:07 (Wind-up release) | |||

| Label | Blue Collar (original) Wind-up (re-release) | |||

| Producer | John Kurzweg | |||

| Creed chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from My Own Prison | ||||

| ||||

My Own Prison is the debut studio album by American rock band Creed, released in 1997. The album was issued independently by the band's record label, Blue Collar Records, on April 14, 1997, and re-released by Wind-up Records on August 26, 1997. Manager Jeff Hanson matched Creed up with John Kurzweg, and My Own Prison was recorded for $6,000, funded by Hanson. The band wrote several songs, trying to discover their own identity, and in their early days, the members had jobs, while bassist Brian Marshall got a degree. Creed began recording music and released the album on their own, distributing it to radio stations in Florida. The band later got a record deal with Wind-up.

At the time of My Own Prison's publication, Creed were compared to several bands, including Soundgarden (especially the Badmotorfinger era), Pearl Jam, Alice in Chains, Hootie & the Blowfish, Tool, and Metallica. Influenced by heavy metal and 1970s stadium rock, My Own Prison's music has been described as grunge, post-grunge, and "slightly heavy metal, slightly alternative". The album is a lot more heavy and grunge-oriented than Creed's subsequent work. Its lyrics include topics like emerging adulthood, self-identity, Christianity and faith, sinning, suicide, unity, struggling to prosper in life, pro-life, and race relations in America. Vocalist Scott Stapp and guitarist Mark Tremonti said their early adulthood inspired lyrics to songs like the title track and "Torn". Stapp was inspired by music by U2 (particularly The Joshua Tree), Led Zeppelin, and the Doors. Influenced by thrash metal bands like Metallica, Slayer, Exodus, and Forbidden, Tremonti brought heavy metal musical elements into Creed's music.

Creed released four singles from the album: the title track, "Torn", "What's This Life For", and "One". Despite only peaking at number 22 on the Billboard 200, strong radio airplay propelled My Own Prison to become a commercial success. All singles were successful on rock radio in the United States and, with the exception of "One", had music videos that received airplay on MTV. My Own Prison was eventually certified sextuple platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America and, as of 2009, sold over 6,000,000 copies in the United States, according to Nielsen SoundScan. The album received reviews ranging from positive to negative, complimenting its guitar riffs and music but criticizing its similarity to 1990s grunge bands.

Background, writing, recording, and production

[edit]For the band's debut release, manager Jeff Hanson matched them up with John Kurzweg, a producer friend who, with his unobtrusive production style and talents as a songwriter and multi-instrumentalist, he felt was a great fit.[1] The album, funded by Hanson, was recorded for $6,000. My Own Prison was originally released independently on the band's own label, Blue Collar Records, in 1997. It was distributed to Florida radio stations, and their enthusiasm for the record helped it sell 6,000 copies in the first two months in Florida alone.[1] Vocalist Scott Stapp said that even though the band was trying to find their creative stride, it took a while for them to discover their musical style. He said in August 2017: "I remember after Mark and I and the guys wrote our first five or seven songs and we hadn't found our identity yet. Then we wrote a song called 'Grip My Soul', which we never recorded or put out but I remember leaving band rehearsal and all of us felt the same way. Like, alright, we found ourselves. We found out who we are and then right after that is when 'My Own Prison' poured out of us". He added: "If I'm remembering correctly, those were essentially the next 10 out of 13 songs that we wrote after that initial 'find your identity' moment that I think every band has".[2] Guitarist Mark Tremonti said that in the band's early days, he was working as a cook at Chili's and Stapp was a cook at Ruby Tuesday's. Drummer Scott Phillips was managing a knife store at a mall and bassist Brian Marshall was the only one without a job, and, according to Tremonti, Marshall "was also the only one who ended up getting his degree before it was all said and done".[3] When Creed got a record deal, the band got an advance, and Tremonti quit his job and started working for about three weeks at the local guitar shop and then after that, Creed began touring.[3] My Own Prison was originally released through Blue Collar Records but was remixed by Wind-up Records and then reissued. Creed recorded the original version of the album in Kurzweg's house in Tallahassee, Florida. To record the rest of the album, they went to Long View Farm in North Brookfield, Massachusetts.[3]

Music and lyrics

[edit]

My Own Prison is a lot heavier and more grunge-oriented than other Creed albums.[5] Its lyrical themes include self-identity, Christianity, faith, sinning, anti-abortion, and anti-affirmative action.[5][6] The music has been described as grunge,[7][6] post-grunge,[8][9] alternative metal,[10] and heavy metal.[11] Jon Parales of The New York Times compared the album to the Badmotorfinger era of Soundgarden. He also likened the music to Hootie & the Blowfish and the song "Unforgiven" to Metallica.[6] Stephen Thomas Erlewine of AllMusic wrote that "Creed don't have an original or distinctive sound—they basically fall into the category of post-Seattle bands who temper their grunge with a dose of Live earnestness".[8] In 1997, when My Own Prison first brought the band attention from the mainstream, Bradley Bambarger of Billboard wrote in December that Creed sound "disconcertingly reminiscent of Alice in Chains".[12] Justin Seremet of the Hartford Courant wrote in 1998 that Creed "is essentially Alice in Chains without the bite", comparing singer Stapp's vocals to that of the deceased AIC vocalist, Layne Staley.[7] He described the album as "scrunge", which he defined as "the adopted name for groups that rode the Seattle wave with a couple of hits and subsequently vanished—bands like Silverchair, Sponge, Candlebox, and so on."[7] In a review of My Own Prison from January 1998, The Spokesman-Review described Creed as "slightly heavy metal, slightly alternative".[10] The New Rolling Stone Album Guide described the record as being influenced by 1970s stadium rock and wrote that it includes "thundering metallic tracks and sweeping ballads".[13] In August 2017, Phil Freeman of Stereogum wrote:

"The music on My Own Prison took ideas from grunge, which had mostly come and gone by that point, and filtered them through more mainstream hard rock and arena metal. Creed weren't interested in the punk rock energy of Mudhoney or Nirvana, but they were borrowing heavily from Pearl Jam and Alice in Chains, whose lugubrious style was a natural fit for Scott Stapp's baritone roar. Their tempos were slow and heavy, especially on the singles, but Mark Tremonti was a full-on shredder—the guitar solo on 'Pity for a Dime' could have come off a Dio album, and album tracks like 'Ode,' 'Unforgiven' and 'Sister' had a pleasingly thick-necked stomp. Lyrically, Creed were plainspoken—poetic, but free of abstraction, a legacy of Stapp's love of earnest frontmen like Jim Morrison and Bono."[3]

Stapp was heavily influenced by U2's 1987 album, The Joshua Tree, as well as by the Doors and Led Zeppelin.[12] The band was frequently compared to Tool, Soundgarden, and Pearl Jam, in response to which, Stapp said: "It could be worse. They could be comparing us to some shitty band that no one has ever heard of, rather than the biggest band of the decade."[5] Likewise, Tremonti stated, "It doesn't bother me so much. They're one of the best bands to come out in the past 10 years."[14][12]

The track "What's This Life For" is about a best friend of Tremonti's who committed suicide, and the guitarist has described it as "a song about suicide and kids searching for that meaning of life".[15] "One", a more catchy and upbeat-sounding track,[2] criticizes society's alleged lack of unity.[16] "Torn", written by Tremonti, is autobiographical. Prior to Creed's success, the guitarist held various jobs to pay for college, including washing cars and working as a cook. "One day, I came home from work at about 3 in the morning," he said. "I was all dirty and stinky and hating my life, so I just wrote a song about what it's like being a kid in between 18 and 23, when you haven't graduated from school yet and you don't know what you're doing with your life." He added: "It's about how hard that period of time is, when you're broke, you have to work two jobs to go to school. I was at a hard point in my life, so I wrote a song about it".[17][14]

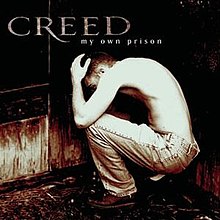

Artwork and packaging

[edit]Prior to releasing the album on their own independent label, Creed recruited Daniel Tremonti, Mark's brother, to become their creative director. Stapp described Daniel as a "super soulful guy with the heart and talent of a true artist". They picked a photo that Daniel had taken for a photography class as the cover for the record. The image was of a man named Justin Brown, a friend of the band, depicting him kneeling shirtless in a corner with his hands on top of his head. Stapp claimed the artwork "captured him to the core" and that it reflected the isolation, conflict, and torture that was driving him as well as seeing hope and feeling that he was like the man in the artwork, "who had been beaten down but could now get up". Looking to have a professional-looking final product, the band acquired a loan from bassist Brian Marshall's father and went to a one-stop company to package and manufacture the record. They ordered five thousand copies and took them to major outlets in Tallahassee. All five thousand were sold within the first month.[18][19]

The original Blue Collar Records version featured the band's original logo, a wordmark inside a roundel, situated to the top right just over Justin Brown, with the album title at the bottom. The Wind-up version featured an updated band wordmark logo in a Mason Serif Regular font, now situated on the top left, with the album title just below that, to the right. The band's updated logo would go on to become their permanent logo, although the font would eventually become slightly more extended on future releases.

Promotion, release, and commercial performance

[edit]"It all came true in an instant. Within a year of that record coming out we were essentially playing arenas in some places. So that album will always have a special place in my heart because it changed my life forever and launched my life and career in the music business."

Stapp on Creed's sudden mainstream success with My Own Prison.[2]

Creed released four singles from My Own Prison: the title track in 1997, "Torn" in early 1998,[2] "What's This Life For" later that year, and "One" in early 1999.[20] All four singles had success on the Mainstream Rock Tracks chart, with all except "Torn" also performing well on Modern Rock Tracks.[20] Because they were not initially sold in the United States, the singles were ineligible for the US Billboard Hot 100. However, by the time "One" was released, that restriction was lifted, and the song became Creed's first to chart, reaching number seventy. "My Own Prison" and "One" also managed to peak at numbers 54 and 49 on the US Billboard Hot 100 Airplay, respectively. The videos for the singles also received airplay on MTV.[21] The Blue Collar Records version of My Own Prison was released on April 14, 1997,[22] and the Wind-up reissue came out on August 26, 1997.[23] In October 2022, a remaster of My Own Prison on vinyl was announced in celebration of the album's 25th anniversary.[24][25] It was issued through Craft Recordings on December 2, 2022.[26]

My Own Prison peaked at number 22 on the Billboard 200 on May 2, 1998, staying on the chart for 112 weeks.[27] The album also peaked at number one on the Heatseekers Albums chart on November 8, 1997.[28] On January 22, 2000, the album reached number one on the Catalog Albums chart, remaining there for 157 weeks.[29] My Own Prison was certified double platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America on August 25, 1998. It went triple platinum on February 26, 1999, 4× platinum on November 3, 1999, 5× platinum on December 4, 2000, and 6× platinum on August 26, 2002.[30] On January 2, 1998, MTV reported that the album had sold 175,000 copies in the United States.[5] On September 18, 1998, The New York Times stated that My Own Prison had sold 2,200,000 copies nationally.[6] Time reported on October 18, 1999, that the record had sold nearly 4,000,000 copies.[31] On January 3, 2002, Rolling Stone wrote that, according to Nielsen SoundScan, My Own Prison sold 5,700,000 copies in the US.[32] My Own Prison was certified sextuple platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America on August 26, 2002, for selling 6,000,000 copies.[33] As of 2009, the album had sold more than 6,000,000 copies in the US, according to Nielsen SoundScan.[34] My Own Prison sold 15,000,000 copies worldwide, making it one of the most successful debut albums of all time.[35]

Critical reception

[edit]| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Cryptic Rock | 5/5[26] |

| Music Critic | 70[36] |

| Rock Hard | |

| The New Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| The Phantom Tollbooth | |

My Own Prison received mixed reviews from critics. AllMusic wrote: "Creed don't have an original or distinctive sound—they basically fall into the category of post-Seattle bands who temper their grunge with a dose of Live earnestness—but they work well within their boundaries. At their best, they are a solid post-grunge band, grinding their riffs out with muscle; at their worst, they are simply faceless. The best moments of My Own Prison suggest they'll be able to leave post-grunge anonymity behind and develop their own signature sound."[8] Trevor Miller of Music Critic described the album as "overall, an excellent first album".[36]

Jon Pareles of The New York Times, with an article entitled "Grunge Gets Religion, and It's Not Pretty", criticized My Own Prison and wrote: "Convictions aside, Creed's weakness is its music. The band's imitation of Soundgarden circa 1991 is a clumsy one."[6] The Spokesman-Review wrote: "I like the CD. I like the band, but there is room for improvement."[10] Justin Seremet of the Hartford Courant panned My Own Prison, stating: "Just as the Warrants and Slaughters of the world hung around long after their brand of music had gone to the grave, so will Creed. Let's move on, folks."[7]

Track listing

[edit]Blue Collar Records version

[edit]All tracks are written by Scott Stapp and Mark Tremonti.[3]

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Torn" | 6:24 |

| 2. | "Ode" | 5:01 |

| 3. | "My Own Prison" | 5:43 |

| 4. | "Pity for a Dime" | 5:38 |

| 5. | "In America" | 5:03 |

| 6. | "Allusion" ("Illusion" is spelled as "Allusion" on the Blue Collar release.) | 4:45 |

| 7. | "Unforgiven" | 3:44 |

| 8. | "Sister" | 5:37 |

| 9. | "What's This Life For" | 4:29 |

| 10. | "One" | 5:27 |

| Total length: | 51:56 | |

Wind-up Records version

[edit]| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Torn" | 6:23 |

| 2. | "Ode" | 4:56 |

| 3. | "My Own Prison" | 4:58 |

| 4. | "Pity for a Dime" | 5:29 |

| 5. | "In America" | 4:58 |

| 6. | "Illusion" | 4:36 |

| 7. | "Unforgiven" | 3:38 |

| 8. | "Sister" | 4:55 |

| 9. | "What's This Life For" | 4:08 |

| 10. | "One" | 5:02 |

| Total length: | 49:07 | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 11. | "Bound and Tied" | 5:35 |

| Total length: | 54:42 | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 11. | "Bound and Tied" | 5:35 |

| 12. | "What's This Life For" (acoustic) | 4:22 |

| Total length: | 59:04 | |

Personnel

[edit]Credits adapted from album liner notes.[39][40]

|

|

Charts

[edit]

Weekly charts[edit]

|

Year-end charts[edit]

Decade-end charts[edit]

|

Certifications

[edit]| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Canada (Music Canada)[55] | 3× Platinum | 300,000^ |

| New Zealand (RMNZ)[56] | 3× Platinum | 45,000^ |

| United States (RIAA)[57] | 6× Platinum | 6,000,000[34] |

|

^ Shipments figures based on certification alone. | ||

Song use

[edit]- "What's This Life For" was featured in the 1998 horror film Halloween H20: 20 Years Later.[58]

- "Bound and Tied" was featured on the soundtrack to the 1998 comedy film Dead Man on Campus.[59]

- "Pity for a Dime" was featured on the soundtrack to the 2000 TV film Jailbait![60]

- "My Own Prison" was featured in the 2002 TV film Bang Bang You're Dead.[61]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Interview With Jeff Hanson". HitQuarters. September 13, 2010. Retrieved October 5, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Childers, Chad (August 26, 2017). "20 Years Ago: Creed Unleash Their Debut Album 'My Own Prison'". Loudwire. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Freeman, Phil (August 25, 2017). "Last of the Multi-Platinum Post-Grunge Bands: Creed Talk My Own Prison at 20". Stereogum. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ "Interview – Mark Tremonti of Alter Bridge". Cryptic Rock. October 15, 2014. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Smith, Dakota (January 2, 1998). "Creed Score With 'My Own Prison'". MTV. Archived from the original on February 26, 2019. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Pareles, Jon (September 18, 1998). "Pop Review; Grunge Gets Religion, and It's Not Pretty". The New York Times. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Seremet, Justin (January 8, 1998). "My Own Prison – Creed". Hartford Courant. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "My Own Prison – Creed". AllMusic.

- ^ Martins, Jorge (December 25, 2023). "Top 10 Post-Grunge Albums from the '90s That Actually Stood the Test of Time". Ultimate Guitar. Archived from the original on December 26, 2023. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ^ a b c "They Sound Good, But Creed's Songs Run a Little Long". January 12, 1998. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ Weingarten, Marc (September 25, 1999). "Record Rack". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- ^ a b c Bambarger, Bradley (December 20, 1997). "The Modern Age". Billboard. Vol. 109, no. 51. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. p. 97. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ a b Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian David (2004). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide. Simon and Schuster. p. 199. ISBN 9780743201698. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ a b c Taylor, Betsy; Ramstetter, Michele (April 10, 1998). "Creed, Up By Its Own Bootstraps". The Buffalo News. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ Derrough, Leslie Michele (September 17, 2015). "Mark Tremonti (Creed, Alter Bridge)". Songfacts. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ "One by Creed". Songfacts. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ "Torn by Creed". Songfacts. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ Ritz, David (September 20, 2012). Sinner's Creed. United States of America: Tyndale House Books. p. 116. ISBN 978-1414364568.

- ^ "Rewind With Rach: Creed "What's This Life For"". 1063radiolafayette.com. 1063 Radio Lafayette. January 13, 2016. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- ^ a b "Creed Writing Material for Next Album, Mulls Rock Package Tour". MTV. February 11, 1999. Archived from the original on April 17, 2021. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ "The Most-Played Clips as Monitored by Broadcast Data Systems". Billboard. Vol. 110, no. 15. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. April 11, 1998. p. 98. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ "My Own Prison by Creed". Rate Your Music. Retrieved July 11, 2024.

- ^ "Creed Biography". Musician Guide. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ "Creed: Re-releasing My Own Prison on Vinyl". Heaven's Metal Magazine. October 25, 2022. Retrieved November 4, 2024.

- ^ Ken, Charles (October 29, 2022). "Creed, My Own Prison', to be available on vinyl for the first time". Audio Ink Radio. Retrieved November 4, 2024.

- ^ a b "Creed – My Own Prison (25th anniversary vinyl review)". Cryptic Rock. December 12, 2022. Retrieved October 1, 2024.

- ^ a b "Creed Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ a b "Creed Chart History (Heatseekers Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ a b "Creed Chart History (Catalog Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ "Gold & Platinum". Recording Industry Association of America.

- ^ Farley, Christopher John (October 18, 1999). "Music: Human Clay". Time. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ Crandall, Bill (January 3, 2002). "Creed Number One for Sixth Week". Rolling Stone. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ "Recording Industry Association of America". RIAA. Retrieved July 1, 2024.

- ^ a b Waddell, Ray (July 22, 2009). "Q&A: Creed's Quest for a Comeback". Billboard. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ Voorman, Joel (May 20, 2017). "Scott Stapp Interview". Cleveland Scene. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ a b Miller, Trevor. "My Own Prison – Album and Concert Reviews @ Music-Critic.com: the source for music reviews, interviews, articles, and news on the internet". Music Critic. Retrieved July 5, 2017.

- ^ Schnädelbach, Buffo. "Review". issue 142 (in German). Rock Hard. Retrieved May 20, 2013.

- ^ Spencer, Josh. "My Own Prison". The Phantom Tollbooth. Retrieved January 25, 2023.

- ^ My Own Prison (booklet). Blue Collar Records. 1997.

- ^ My Own Prison (booklet). Wind-up Records. 1997. p. 7.

- ^ Ryan, Gavin (2011). Australia's Music Charts 1988–2010 (PDF ed.). Mt Martha, Victoria, Australia: Moonlight Publishing. p. 69.

- ^ "Austriancharts.at – Creed – My Own Prison" (in German). Hung Medien. Retrieved November 14, 2021.

- ^ "Top RPM Albums: Issue 3483". RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved November 14, 2021.

- ^ "Dutchcharts.nl – Creed – My Own Prison" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved September 9, 2023.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – Creed – My Own Prison" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved November 14, 2021.

- ^ "Charts.nz – Creed – My Own Prison". Hung Medien. Retrieved November 14, 2021.

- ^ "Swisscharts.com – Creed – My Own Prison". Hung Medien. Retrieved November 14, 2021.

- ^ "Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End (1998)". Billboard. Archived from the original on January 5, 2018. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ "Top Selling Albums of 1999". Recorded Music NZ. Archived from the original on December 3, 2020. Retrieved November 16, 2021.

- ^ "Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End (1999)". Billboard. Archived from the original on January 5, 2018. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ "The Year in Music 2000 – Top Pop Catalog Albums". Billboard. Vol. 112, no. 53. December 30, 2000. p. YE-86. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved June 1, 2022 – via Google Books.

- ^ "The Year in Music 2001 – Top Pop Catalog Albums". Billboard. Vol. 113, no. 52. December 29, 2001. p. YE-69. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved June 1, 2022 – via Google Books.

- ^ "The Year in Music 2002 – Top Pop Catalog Albums". Billboard. Vol. 114, no. 52. December 28, 2002. p. YE-86. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved June 1, 2022 – via Google Books.

- ^ "1999 The Year in Music – Totally '90s: Diary of a Decade – Top Pop Albums of the '90s". Billboard. Vol. 111, no. 52. December 25, 1999. p. YE-20. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved June 1, 2022 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Canadian album certifications – Creed – My Own Prison". Music Canada. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ "New Zealand album certifications – Creed – My Own Prison". Recorded Music NZ. Retrieved October 20, 2020.[dead link]

- ^ "American album certifications – Creed – My Own Prison". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ "What's This Life For". songfacts.com. Songfacts. Retrieved October 13, 2024.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Dead Man on Campus Original Soundtrack". AllMusic. All Media Network. Retrieved October 13, 2024.

- ^ Henderson, Alex. "Jailbait!: Music from the MTV Original TV Movie Original TV Soundtrack". AllMusic. All Media Network. Retrieved October 13, 2024.

- ^ Childers, Chad (August 26, 2017). "20 Years Ago: Creed Unleash Their Debut Album 'My Own Prison'". Loudwire. Retrieved October 13, 2024.