Byzantine Empire

Byzantine Empire | |

|---|---|

| 330–1453 | |

The empire in 555 under Justinian I, its greatest extent since the fall of the Western Roman Empire, with vassals in pink | |

| Capital | Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) |

| Common languages | |

| Religion | Christianity (official) |

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Government | Autocracy |

| Notable emperors | |

• 306–337 | Constantine I |

• 379–395 | Theodosius I |

• 408–450 | Theodosius II |

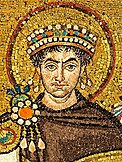

• 527–565 | Justinian I |

• 610–641 | Heraclius |

• 717–741 | Leo III |

• 976–1025 | Basil II |

• 1081–1118 | Alexios I |

• 1143–1180 | Manuel I |

• 1261–1282 | Michael VIII |

• 1449–1453 | Constantine XI |

| Historical era | Late antiquity to Late Middle Ages |

| Population | |

• 457 | 16,000,000 |

• 565 | 26,000,000 |

• 775 | 7,000,000 |

• 1025 | 12,000,000 |

• 1320 | 2,000,000 |

| Currency | Solidus, denarius, and hyperpyron |

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred in Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. The eastern half of the Empire survived the conditions that caused the fall of the West in the 5th century AD, and continued to exist until the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire in 1453. During most of its existence, the empire remained the most powerful economic, cultural, and military force in the Mediterranean world. The term "Byzantine Empire" was only coined following the empire's demise; its citizens referred to the polity as the "Roman Empire" and to themselves as "Romans".[a] Due to the imperial seat's move from Rome to Byzantium, the adoption of state Christianity, and the predominance of Greek instead of Latin, modern historians continue to make a distinction between the earlier Roman Empire and the later Byzantine Empire.

During the earlier Pax Romana period, the western parts of the empire became increasingly Latinised, while the eastern parts largely retained their preexisting Hellenistic culture. This created a dichotomy between the Greek East and Latin West. These cultural spheres continued to diverge after Constantine I (r. 324–337) moved the capital to Constantinople and legalised Christianity. Under Theodosius I (r. 379–395), Christianity became the state religion, and other religious practices were proscribed. Greek gradually replaced Latin for official use as Latin fell into disuse.

The empire experienced several cycles of decline and recovery throughout its history, reaching its greatest extent after the fall of the west during the reign of Justinian I (r. 527–565), who briefly reconquered much of Italy and the western Mediterranean coast. The appearance of plague and a devastating war with Persia exhausted the empire's resources; the early Muslim conquests that followed saw the loss of the empire's richest provinces—Egypt and Syria—to the Rashidun Caliphate. In 698, Africa was lost to the Umayyad Caliphate, but the empire subsequently stabilised under the Isaurian dynasty. The empire was able to expand once more under the Macedonian dynasty, experiencing a two-century-long renaissance. This came to an end in 1071, with the defeat by the Seljuk Turks at the Battle of Manzikert. Thereafter, periods of civil war and Seljuk incursion resulted in the loss of most of Asia Minor. The empire recovered during the Komnenian restoration, and Constantinople would remain the largest and wealthiest city in Europe until the 13th century.

The empire was largely dismantled in 1204, following the Sack of Constantinople by Latin armies at the end of the Fourth Crusade; its former territories were then divided into competing Greek rump states and Latin realms. Despite the eventual recovery of Constantinople in 1261, the reconstituted empire would wield only regional power during its final two centuries of existence. Its remaining territories were progressively annexed by the Ottomans in perennial wars fought throughout the 14th and 15th centuries until Constantinople fell in 1453, putting an end to the empire. The fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453 ultimately brought the empire to an end. Many refugees who had fled the city after its capture settled in Italy and throughout Europe, helping to ignite the Renaissance. The fall of Constantinople is sometimes used to mark the dividing line between the Middle Ages and the early modern period.

Nomenclature

The inhabitants of the empire, now generally termed Byzantines, thought of themselves as Romans (Romaioi). Their Islamic neighbours similarly called their empire the "land of the Romans" (Bilād al-Rūm), but the people of medieval Western Europe preferred to call them "Greeks" (Graeci), due to having a contested legacy to Roman identity and to associate negative connotations from ancient Latin literature.[1] The adjective "Byzantine", which derived from Byzantion (Latinised as Byzantium), the name of the Greek settlement Constantinople was established on, was only used to describe the inhabitants of that city; it did not refer to the empire, which they called Romanía—"Romanland".[2]

After the empire's fall, early modern scholars referred to the empire by many names, including the "Empire of Constantinople", the "Empire of the Greeks", the "Eastern Empire", the "Late Empire", the "Low Empire", and the "Roman Empire".[3] The increasing use of "Byzantine" and "Byzantine Empire" likely started with the 15th-century historian Laonikos Chalkokondyles, whose works were widely propagated, including by Hieronymus Wolf. "Byzantine" was used adjectivally alongside terms such as "Empire of the Greeks" until the 19th century.[4] It is now the primary term, used to refer to all aspects of the empire; some modern historians believe that, as an originally prejudicial and inaccurate term, it should not be used.[5]

History

As the historiographical periodizations of "Roman history", "late antiquity", and "Byzantine history" significantly overlap, there is no consensus on a "foundation date" for the Byzantine Empire, if there was one at all. The growth of the study of "late antiquity" has led to some historians setting a start date in the seventh or eighth centuries.[6] Others believe a "new empire" began during changes in c. 300 AD.[7] Still others hold that these starting points are too early or too late, and instead begin c. 500.[8] Geoffrey Greatrex believes that it is impossible to precisely date the foundation of the Byzantine Empire.[9]

Early history (pre-518)

In a series of conflicts between the third and first centuries BC, the Roman Republic gradually established hegemony over the eastern Mediterranean, while its government ultimately transformed into the one-person rule of an emperor. The Roman Empire enjoyed a period of relative stability until the third century AD, when a combination of external threats and internal instabilities caused the Roman state to splinter as regional armies acclaimed their generals as "soldier-emperors".[10] One of these, Diocletian (r. 284–305), seeing that the state was too big to be ruled by one man, attempted to fix the problem by instituting a Tetrarchy, or rule of four, and dividing the empire into eastern and western halves. Although the Tetrarchy system quickly failed, the division of the empire proved an enduring concept.[11]

Constantine I (r. 306–337) secured sole power in 324. Over the following six years, he rebuilt the city of Byzantium as a capital city, which was renamed Constantinople. Rome, the previous capital, was further from the important eastern provinces and in a less strategically important location; it was not esteemed by the "soldier-emperors" who ruled from the frontiers or by the empire's population who, having been granted citizenship, considered themselves "Roman".[12] Constantine extensively reformed the empire's military and civil administration and instituted the gold solidus as a stable currency.[13] He favoured Christianity, which he had converted to in 312.[14] Constantine's dynasty fought a lengthy conflict against Sasanid Persia and ended in 363 with the death of his son-in-law Julian.[15] The short Valentinianic dynasty, occupied with wars against barbarians, religious debates, and anti-corruption campaigns, ended in the East with the death of Valens at the Battle of Adrianople in 378.[16]

Valens's successor, Theodosius I (r. 379–395), restored political stability in the east by allowing the Goths to settle in Roman territory;[17] he also twice intervened in the western half, defeating the usurpers Magnus Maximus and Eugenius in 388 and 394 respectively.[18] He actively condemned paganism, confirmed the primacy of Nicene Christianity over Arianism, and established Christianity as the Roman state religion.[19] He was the last emperor to rule both the western and eastern halves of the empire;[20] after his death, the West would be destabilised by a succession of "soldier-emperors", unlike the East, where administrators would continue to hold power. Theodosius II (r. 408–450) largely left the rule of the east to officials such as Anthemius, who constructed the Theodosian Walls to defend Constantinople, now firmly entrenched as Rome's capital.[21]

Theodosius' reign was marked by the theological dispute over Nestorianism, which was eventually deemed heretical, and by the formulation of the Codex Theodosianus law code.[22] It also saw the arrival of Attila's Huns, who ravaged the Balkans and exacted a massive tribute from the empire; Attila however switched his attention to the rapidly-deteriorating western empire, and his people fractured after his death in 453.[23] After Leo I (r. 457–474) failed in his 468 attempt to reconquer the west, the warlord Odoacer deposed Romulus Augustulus in 476, killed his titular successor Julius Nepos in 480, and the office of western emperor was formally abolished.[24]

Through a combination of luck, cultural factors, and political decisions, the Eastern empire never suffered from rebellious barbarian vassals and was never ruled by barbarian warlords—the problems which ensured the downfall of the West.[25] Zeno (r. 474–491) convinced the problematic Ostrogoth king Theodoric to take control of Italy from Odoacer, which he did; dying with the empire at peace, Zeno was succeeded by Anastasius I (r. 491–518).[26] Although his Monophysitism brought occasional issues, Anastasius was a capable administrator and instituted several successful financial reforms including the abolition of the chrysargyron tax. He was the first emperor to die with no serious problems affecting his empire since Diocletian.[27]

518–717

The reign of Justinian I was a watershed in Byzantine history.[28] Following his accession in 527, the law-code was rewritten as the influential Corpus Juris Civilis and Justinian produced extensive legislation on provincial administration;[29] he reasserted imperial control over religion and morality through purges of non-Christians and "deviants";[30] and having ruthlessly subdued the 532 Nika revolt he rebuilt much of Constantinople, including the original Hagia Sophia.[31] Justinian took advantage of political instability in Italy to attempt the reconquest of lost western territories. The Vandal Kingdom in North Africa was subjugated in 534 by the general Belisarius, who then invaded Italy; the Ostrogothic Kingdom was destroyed in 554.[32]

In the 540s, however, Justinian began to suffer reversals on multiple fronts. Taking advantage of Constantinople's preoccupation with the West, Khosrow I of the Sasanian Empire invaded Byzantine territory and sacked Antioch in 540.[33] Meanwhile, the emperor's internal reforms and policies began to falter, not helped by a devastating plague that killed a large proportion of the population and severely weakened the empire's social and financial stability.[34] The most difficult period of the Ostrogothic war, against their king Totila, came during this decade, while divisions among Justinian's advisors undercut the administration's response.[35] He also did not fully heal the divisions in Chalcedonian Christianity, as the Second Council of Constantinople failed to make a real difference.[36] Justinian died in 565; his reign saw more success than that of any other Byzantine emperor, yet he left his empire under massive strain.[37]

Financially and territorially overextended, Justin II (r. 565–578) was soon at war on many fronts. The Lombards, fearing the aggressive Avars, conquered much of northern Italy by 572.[38] The Sasanian wars restarted that year, and continued until the emperor Maurice finally emerged victorious in 591; by that time, the Avars and Slavs had repeatedly invaded the Balkans, causing great instability.[39] Maurice campaigned extensively in the region during the 590s, but although he managed to re-establish Byzantine control up to the Danube, he pushed his troops too far in 602—they mutinied, proclaimed an officer named Phocas as emperor, and executed Maurice.[40] The Sasanians seized their moment and reopened hostilities; Phocas was unable to cope and soon faced a major rebellion led by Heraclius. Phocas lost Constantinople in 610 and was soon executed, but the destructive civil war accelerated the empire's decline.[41]

Bottom: the Theodosian Walls of Constantinople, critically important during the 717–718 siege.

Under Khosrow II, the Sassanids occupied the Levant and Egypt and pushed into Asia Minor, while Byzantine control of Italy slipped and the Avars and Slavs ran riot in the Balkans.[42] Although Heraclius repelled a siege of Constantinople in 626 and defeated the Sassanids in 627, this was a pyrrhic victory.[43] The early Muslim conquests soon saw the conquest of the Levant, Egypt, and the Sassanid Empire by the newly-formed Arabic Rashidun Caliphate.[44] By Heraclius' death in 641, the empire had been severely reduced economically as well as territorially—the loss of the wealthy eastern provinces had deprived Constantinople of three-quarters of its revenue.[45]

The next seventy-five years are poorly documented.[46] Arab raids into Asia Minor began almost immediately, and the Byzantines resorted to holding fortified centres and avoiding battle at all costs; although it was invaded annually, Anatolia avoided permanent Arab occupation.[47] The outbreak of the First Fitna in 656 gave Byzantium breathing space, which it used wisely: some order was restored in the Balkans by Constans II (r. 641–668),[48] who began the administrative reorganisation known as the "theme system", in which troops were allocated to defend specific provinces.[49] With the help of the recently rediscovered Greek fire, Constantine IV (r. 668–685) repelled the Arab efforts to capture Constantinople in the 670s,[50] but suffered a reversal against the Bulgars, who soon established an empire in the northern Balkans.[51] Nevertheless, he and Constans had done enough to secure the empire's position, especially as the Umayyad Caliphate was undergoing another civil war.[52]

Justinian II sought to build on the stability secured by his father Constantine but was overthrown in 695 after attempting to exact too much from his subjects; over the next twenty-two years, six more rebellions followed in an era of political instability.[53] The reconstituted caliphate sought to break Byzantium by taking Constantinople, but the newly crowned Leo III managed to repel the 717–718 siege, the first major setback of the Muslim conquests.[54]

718–867

Leo and his son Constantine V (r. 741–775), two of the most capable Byzantine emperors, withstood continued Arab attacks, civil unrest, and natural disasters, and reestablished the state as a major regional power.[55] Leo's reign produced the Ecloga, a new code of law to succeed that of Justinian II,[56] and continued to reform the "theme system" in order to lead offensive campaigns against the Muslims, culminating in a decisive victory in 740.[57] Constantine overcame an early civil war against his brother-in-law Artabasdos, made peace with the new Abbasid Caliphate, campaigned successfully against the Bulgars, and continued to make administrative and military reforms.[58] However, due to both emperors' support for the Byzantine Iconoclasm, which opposed the use of religious icons, they were later vilified by Byzantine historians;[59] Constantine's reign also saw the loss of Ravenna to the Lombards, and the beginning of a split with the Roman papacy.[60]

In 780, Empress Irene assumed power on behalf of her son Constantine VI.[61] Although she was a capable administrator who temporarily resolved the iconoclasm controversy,[62] the empire was destabilized by her feud with her son. The Bulgars and Abbasids meanwhile inflicted numerous defeats on the Byzantine armies, and the papacy crowned Charlemagne as Roman emperor in 800.[63] In 802, the unpopular Irene was overthrown by Nikephoros I; he reformed the empire's administration but died in battle against the Bulgars in 811.[64] Military defeats and societal disorder, especially the resurgence of iconoclasm, characterised the next eighteen years.[65]

Stability was somewhat restored during the reign of Theophilos (r. 829–842), who exploited economic growth to complete construction programs, including rebuilding the sea walls of Constantinople, overhaul provincial governance, and wage inconclusive campaigns against the Abbasids.[66] After his death, his empress Theodora, ruling on behalf of her son Michael III, permanently extinguished the iconoclastic movement;[67] the empire prospered under their sometimes-fraught rule. However, Michael was posthumously vilified by historians loyal to the dynasty of his successor Basil I, who assassinated him in 867 and who was given credit for his predecessor's achievements.[68]

867–1081

Basil I (r. 867–886) continued Michael's policies.[69] His armies campaigned with mixed results in Italy but defeated the Paulicians of Tephrike.[70] His successor Leo VI (r. 886–912)[b] compiled and propagated a huge number of written works. These included the Basilika, a Greek translation of Justinian I's law-code which included over 100 new laws of Leo's devising; the Tactica, a military treatise; and the Book of the Eparch, which codified Constantinople's trading regulations.[72] In non-literary contexts Leo was less successful: the empire lost in Sicily and against the Bulgarians,[73] while he provoked theological scandal by marrying four times in an attempt to father a legitimate heir.[74]

The early reign of Leo's young heir, Constantine VII, was tumultuous, as his mother Zoe, the patriarch Nicholas, the powerful Simeon I of Bulgaria, and other influential figures jockeyed for power.[75] In 920, the admiral Romanos I used his fleet to secure power, crowning himself and demoting Constantine to the position of junior co-emperor.[76]

Between 1021 and 1022, following years of tensions, Basil II led a series of victorious campaigns against the Kingdom of Georgia, resulting in the annexation of several Georgian provinces to the empire. Basil's successors also annexed Bagratid Armenia in 1045. Importantly, both Georgia and Armenia were significantly weakened by the Byzantine administration's policy of heavy taxation and abolishing of the levy. The weakening of Georgia and Armenia played a significant role in the Byzantine defeat at Manzikert in 1071.[77]

Basil II is considered among the most capable Byzantine emperors and his reign as the apex of the empire in the Middle Ages. By 1025, the date of Basil II's death, the Byzantine Empire stretched from Armenia in the east to Calabria in southern Italy in the west.[78] Many successes had been achieved, ranging from the conquest of Bulgaria to the annexation of parts of Georgia and Armenia, and the reconquests of Crete, Cyprus, and the important city of Antioch. These were not temporary tactical gains but long-term reconquests.[79]

The Byzantine Empire then fell into a period of difficulties, caused to a large extent by the undermining of the theme system and the neglect of the military. Nikephoros II, John Tzimiskes, and Basil II shifted the emphasis of the military divisions (τάγματα, tagmata) from a reactive, defence-oriented citizen army into an army of professional career soldiers, increasingly dependent on foreign mercenaries. Mercenaries were expensive, however, and as the threat of invasion receded in the 10th century, so did the need for maintaining large garrisons and expensive fortifications.[80] Basil II left a burgeoning treasury upon his death, but he neglected to plan for his succession. None of his immediate successors had any particular military or political talent, and the imperial administration increasingly fell into the hands of the civil service. Incompetent efforts to revive the Byzantine economy resulted in severe inflation and a debased gold currency. The army was seen as both an unnecessary expense and a political threat. Several standing local units were demobilised, further augmenting the army's dependence on mercenaries, who could be retained and dismissed on an as-needed basis.[81]

At the same time, Byzantium was faced with new enemies. Its provinces in southern Italy were threatened by the Normans who arrived in Italy at the beginning of the 11th century. During a period of strife between Constantinople and Rome culminating in the East-West Schism of 1054, the Normans advanced gradually into Byzantine Italy.[82] Reggio, the capital of the tagma of Calabria, was captured in 1060 by Robert Guiscard, followed by Otranto in 1068. Bari, the main Byzantine stronghold in Apulia, was besieged in August 1068 and fell in April 1071.[83]

About 1053, Constantine IX disbanded what the historian John Skylitzes calls the "Iberian Army", which consisted of 50,000 men, and it was turned into a contemporary Drungary of the Watch. Two other knowledgeable contemporaries, the former officials Michael Attaleiates and Kekaumenos, agree with Skylitzes that by demobilising these soldiers, Constantine did catastrophic harm to the empire's eastern defences. The emergency lent weight to the military aristocracy in Anatolia, who in 1068 secured the election of one of their own, Romanos Diogenes, as emperor. In the summer of 1071, Romanos undertook a massive eastern campaign to draw the Seljuks into a general engagement with the Byzantine army. At the Battle of Manzikert, Romanos suffered a surprise defeat against Sultan Alp Arslan and was captured. Alp Arslan treated him with respect and imposed no harsh terms on the Byzantines.[81] In Constantinople a coup put in power Michael Doukas, who soon faced the opposition of Nikephoros Bryennios and Nikephoros III Botaneiates. By 1081, the Seljuks had expanded their rule over virtually the entire Anatolian plateau from Armenia in the east to Bithynia in the west, and had established their capital at Nicaea, just 90 kilometres (56 miles) from Constantinople.[84]

Komnenian dynasty and the Crusades

Alexios I and the First Crusade

The Komnenian dynasty attained full power under Alexios I in 1081. From the outset of his reign, Alexios faced a formidable attack from the Normans under Guiscard and his son Bohemund of Taranto, who captured Dyrrhachium and Corfu and laid siege to Larissa in Thessaly. Guiscard's death in 1085 temporarily eased the Norman problem. The following year, the Seljuq sultan died, and the sultanate was split due to internal rivalries. By his own efforts, Alexios defeated the Pechenegs, who were caught by surprise and annihilated at the Battle of Levounion on 28 April 1091.[85]

Having achieved stability in the West, Alexios could turn his attention to the severe economic difficulties and the disintegration of the empire's traditional defences.[86] However, he still did not have enough manpower to recover the lost territories in Asia Minor and to the advance by the Seljuks. At the Council of Piacenza in 1095, envoys from Alexios spoke to Pope Urban II about the suffering of the Christians of the East and underscored that without help from the West, they would continue to suffer under Muslim rule. Urban saw Alexios' request as a dual opportunity to cement Western Europe and reunite the Eastern Orthodox Church with the Roman Catholic Church under his rule.[87] On 27 November 1095, Urban called the Council of Clermont and urged all those present to take up arms under the sign of the Cross and launch an armed pilgrimage to recover Jerusalem and the East from the Muslims. The response in Western Europe was overwhelming.[85] Alexios was able to recover a number of important cities, islands and much of western Asia Minor. The Crusaders agreed to become Alexios' vassals under the Treaty of Devol in 1108, which marked the end of the Norman threat during Alexios' reign.[88][89]

John II, Manuel I, and the Second Crusade

Alexios's son John II Komnenos succeeded him in 1118 and ruled until 1143. John was a pious and dedicated emperor who was determined to undo the damage to the empire suffered at the Battle of Manzikert half a century earlier.[90] Famed for his piety and his remarkably mild and just reign, John was an exceptional example of a moral ruler at a time when cruelty was the norm.[91] For this reason, he has been called the Byzantine Marcus Aurelius. During his twenty-five-year reign, John made alliances with the Holy Roman Empire in the West and decisively defeated the Pechenegs at the Battle of Beroia.[92] He thwarted Hungarian and Serbian threats during the 1120s, and in 1130 he allied himself with Lothair III, the German Emperor against the Norman King Roger II of Sicily.[93]

In the later part of his reign, John focused his activities on the East, personally leading numerous campaigns against the Turks in Asia Minor. His campaigns fundamentally altered the balance of power in the East, forcing the Turks onto the defensive, while retaking many towns, fortresses, and cities across the peninsula for the Byzantines. He defeated the Danishmend Emirate of Melitene and reconquered all of Cilicia,[94] while forcing Raymond of Poitiers, Prince of Antioch, to recognise Byzantine suzerainty.[95] In an effort to demonstrate the emperor's role as the leader of the Christian world, John marched into the Holy Land at the head of the combined forces of the empire and the Crusader states; yet despite his efforts in leading the campaign, his hopes were disappointed by the treachery of his Crusader allies.[96] In 1142, John returned to press his claims to Antioch, but he died in the spring of 1143 following a hunting accident.[97]

John's chosen heir was his fourth son, Manuel I Komnenos, who campaigned aggressively against his neighbours both in the west and east. In Palestine, Manuel allied with the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem and sent a large fleet to participate in a combined invasion of Fatimid Egypt. Manuel reinforced his position as overlord of the Crusader states, with his hegemony over Antioch and Jerusalem secured by agreement with Raynald, Prince of Antioch, and Amalric of Jerusalem.[98] In an effort to restore Byzantine control over the ports of southern Italy, he sent an expedition to Italy in 1155, but disputes within the coalition led to the eventual failure of the campaign. Despite this military setback, Manuel's armies successfully invaded the southern parts of the Kingdom of Hungary in 1167, defeating the Hungarians at the Battle of Sirmium. By 1168, nearly the whole of the eastern Adriatic coast lay in Manuel's hands.[99] Manuel made several alliances with the pope and Western Christian kingdoms, and he successfully handled the passage of the crusaders through his empire.[100]

In the East, Manuel suffered a major defeat in 1176 at the Battle of Myriokephalon against the Turks. These losses were quickly recovered, and in the following year Manuel's forces inflicted a defeat upon a force of "picked Turks".[101] The Byzantine commander John Vatatzes, who destroyed the Turkish invaders at the Battle of Hyelion and Leimocheir, brought troops from the capital and was able to gather an army along the way, a sign that the Byzantine army remained strong and that the defensive program of western Asia Minor was still successful.[102] John and Manuel pursued active military policies, and both deployed considerable resources on sieges and city defences; aggressive fortification policies were at the heart of their imperial military policies.[103] Despite the defeat at Myriokephalon, the policies of Alexios, John and Manuel resulted in vast territorial gains, increased frontier stability in Asia Minor, and secured the stabilisation of the empire's European frontiers. From c. 1081 to c. 1180, the Komnenian army assured the empire's security, enabling Byzantine civilisation to flourish.[104]

This allowed the Western provinces to achieve an economic revival that continued until the close of the century. It has been argued that Byzantium under the Komnenian rule was more prosperous than at any time since the Persian invasions of the 7th century. During the 12th century, population levels rose and extensive tracts of new agricultural land were brought into production. Archaeological evidence from both Europe and Asia Minor shows a considerable increase in the size of urban settlements, together with a notable upsurge in new towns. Trade was also flourishing; the Venetians, the Genoese and others opened up the ports of the Aegean to commerce, shipping goods from the Crusader states and Fatimid Egypt to the west and trading with the empire via Constantinople.[105]

Decline and disintegration

Angelid dynasty

Manuel's death on 24 September 1180 left his 11-year-old son Alexios II Komnenos on the throne. Alexios was highly incompetent in the office, and with his mother Maria of Antioch's Frankish background, his regency was unpopular.[106] Eventually, Andronikos I Komnenos, a grandson of Alexios I, overthrew Alexios II in a violent coup d'état. After eliminating his potential rivals, he had himself crowned as co-emperor in September 1183. He eliminated Alexios II and took his 12-year-old wife Agnes of France for himself.[107]

Andronikos began his reign well; in particular, the measures he took to reform the government of the empire have been praised by historians. According to the historian George Ostrogorsky, Andronikos was determined to root out corruption: under his rule, the sale of offices ceased; selection was based on merit, rather than favouritism; and officials were paid an adequate salary to reduce the temptation of bribery. In the provinces, Andronikos's reforms produced a speedy and marked improvement.[108] Gradually, however, Andronikos's reign deteriorated. The aristocrats were infuriated against him, and to make matters worse, Andronikos seemed to have become increasingly unbalanced; executions and violence became increasingly common, and his reign turned into a reign of terror.[109] Andronikos seemed almost to seek the extermination of the aristocracy as a whole. The struggle against the aristocracy turned into wholesale slaughter, while the emperor resorted to ever more ruthless measures to shore up his regime.[108]

Despite his military background, Andronikos failed to deal with Isaac Komnenos of Cyprus, Béla III of Hungary who reincorporated Croatian territories into Hungary, and Stephen Nemanja of Serbia who declared his independence from the Byzantine Empire. Yet, none of these troubles compared to William II of Sicily's invasion force of 300 ships and 80,000 men, arriving in 1185 and sacking Thessalonica.[110] Andronikos mobilised a small fleet of 100 ships to defend the capital, but other than that he was indifferent to the populace. He was finally overthrown when Isaac II Angelos, surviving an imperial assassination attempt, seized power with the aid of the people and had Andronikos killed.[111]

The reign of Isaac II, and more so that of his brother Alexios III, saw the collapse of what remained of the centralised machinery of Byzantine government and defence. Although the Normans were driven out of Greece, in 1186 the Vlachs and Bulgars began a rebellion that led to the formation of the Second Bulgarian Empire. The internal policy of the Angeloi was characterised by the squandering of the public treasure and fiscal maladministration. Imperial authority was severely weakened, and the growing power vacuum at the centre of the empire encouraged fragmentation. There is evidence that some Komnenian heirs had set up a semi-independent state in Trebizond before 1204.[112] According to the historian Alexander Vasiliev, "the dynasty of the Angeloi, Greek in its origin, ... accelerated the ruin of the Empire, already weakened without and disunited within."[113]

Fourth Crusade and aftermath

In 1198, Pope Innocent III broached the subject of a new crusade through legates and encyclical letters.[114] The stated intent of the crusade was to conquer Egypt, the centre of Muslim power in the Levant. The Crusader army arrived at Venice in the summer of 1202 and hired the Venetian fleet to transport them to Egypt. As a payment to the Venetians, they captured the (Christian) port of Zara in Dalmatia, which was a vassal city of Venice, it had rebelled and placed itself under Hungary's protection in 1186.[115] Shortly afterward, Alexios IV Angelos, son of the deposed and blinded Emperor Isaac II, made contact with the Crusaders. Alexios offered to reunite the Byzantine church with Rome, pay the Crusaders 200,000 silver marks, join the crusade, and provide all the supplies they needed to reach Egypt.[116]

The crusaders arrived at Constantinople in the summer of 1203 and quickly attacked, starting a major fire that damaged large parts of the city, and briefly seized control. Alexios III fled from the capital, and Alexios Angelos was elevated to the throne as Alexios IV along with his blind father Isaac. Alexios IV and Isaac II were unable to keep their promises and were deposed by Alexios V. The crusaders again took the city on 13 April 1204, and Constantinople was subjected to pillage and massacre by the rank and file for three days. Many priceless icons, relics and other objects later turned up in Western Europe, a large number in Venice. According to chronicler Niketas Choniates, a prostitute was even set up on the patriarchal throne.[117] When order had been restored, the crusaders and the Venetians proceeded to implement their agreement; Baldwin of Flanders was elected emperor of a new Latin Empire, and the Venetian Thomas Morosini was chosen as patriarch. The lands divided up among the leaders included most of the former Byzantine possessions.[118] Although Venice was more interested in commerce than conquering territory, it took key areas of Constantinople, and the Doge took the title of "Lord of a Quarter and Half a Quarter of the Roman Empire".[119]

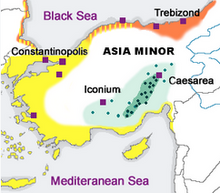

After the sack of Constantinople in 1204 by Latin crusaders, two Byzantine successor states were established: the Empire of Nicaea and the Despotate of Epirus. A third, the Empire of Trebizond, was created after Alexios I of Trebizond, commanding the Georgian expedition in Chaldia[120] a few weeks before the sack of Constantinople, found himself de facto emperor and established himself in Trebizond. Of the three successor states, Epirus and Nicaea stood the best chance of reclaiming Constantinople. The Nicaean Empire struggled to survive the next few decades, however, and by the mid-13th century it had lost much of southern Anatolia.[121] The weakening of the Sultanate of Rûm following the Mongol invasion in 1242–1243 allowed many beyliks and ghazis to set up their own principalities in Anatolia, weakening the Byzantine hold on Asia Minor.[122] Two centuries later, one of the Beys of these beyliks, Osman I, would establish the Ottoman Empire that would eventually conquer Constantinople.[123] However, the Mongol invasion also gave Nicaea a temporary respite from Seljuk attacks, allowing it to concentrate on the Latin Empire to its north.

The Empire of Nicaea, founded by the Laskarid dynasty, managed to recapture Constantinople in 1261 and defeat Epirus. This led to a short-lived revival of Byzantine fortunes under Michael VIII Palaiologos, but the war-ravaged empire was ill-equipped to deal with the enemies that surrounded it. To maintain his campaigns against the Latins, Michael pulled troops from Asia Minor and levied crippling taxes on the peasantry, causing much resentment.[124] Massive construction projects were completed in Constantinople to repair the damage of the Fourth Crusade, but none of these initiatives were of any comfort to the farmers in Asia Minor suffering raids from Muslim ghazis.[125]

Rather than holding on to his possessions in Asia Minor, Michael chose to expand the empire, gaining only short-term success. To avoid another sacking of the capital by the Latins, he forced the Church to submit to Rome, again a temporary solution for which the peasantry hated Michael and Constantinople.[125] The efforts of Andronikos II and later his grandson Andronikos III marked Byzantium's last genuine attempts to restoring the glory of the empire. However, the use of mercenaries by Andronikos II often backfired, with the Catalan Company ravaging the countryside and increasing resentment towards Constantinople.[126]

Fall

The situation became worse for Byzantium during the civil wars after Andronikos III died. A six-year-long civil war devastated the empire, allowing the Serbian ruler Stefan Dušan to overrun most of the empire's remaining territory and establish a Serbian Empire. In 1354, an earthquake at Gallipoli devastated the fort, allowing the Ottomans (who were hired as mercenaries during the civil war by John VI Kantakouzenos) to establish themselves in Europe.[127][128] By the time the Byzantine civil wars had ended, the Ottomans had defeated the Serbians and subjugated them as vassals. Following the Battle of Kosovo, much of the Balkans became dominated by the Ottomans.[129]

Constantinople by this stage was underpopulated and dilapidated. The population of the city had collapsed so severely that it was now little more than a cluster of villages separated by fields. On 2 April 1453, Sultan Mehmed's army of 80,000 men and large numbers of irregulars laid siege to the city.[130] Despite a desperate last-ditch defence of the city by the massively outnumbered Christian forces (c. 7,000 men, 2,000 of whom were foreign),[131] Constantinople finally fell to the Ottomans after a two-month siege on 29 May 1453. The final Byzantine emperor, Constantine XI Palaiologos, was last seen casting off his imperial regalia and throwing himself into hand-to-hand combat after the walls of the city were taken.[132]

Geography

The Empire was centred in what is now Greece and Turkey with Constantinople as its capital.[133] In the 5th century, it controlled the eastern basis of the Mediterranean running east from Singidunum (modern Belgrade) in a line through the Adriatic Sea and south to Cyrene, Libya.[134] This encompassed most of the Balkans, all of modern Greece, Turkey, Syria, Palestine; North Africa, primarily with modern Egypt and Libya; the Aegean islands along with Crete, Cyprus and Sicily, and a small settlement in Crimea.[133]

The landscape of the Empire was defined by the fertile fields of Anatolia, long mountain ranges and rivers such as the Danube.[135] In the north and west were the Balkans, the corridors between the mountain ranges of Pindos, the Dinaric Alps, the Rhodopes and the Balkans. In the south and east were Anatolia, the Pontic Mountains and the Taurus-Anti-Taurus range, which served as passages for armies, while the Caucasus mountains lay between the Empire and its eastern neighbours.[136]

Roman roads connected the Empire by land, with the Via Egnatia running from Constantinople to the Albanian coast through Macedonia and the Via Traiana to Adrianople (modern Edirne), Serdica (modern Sofia) and Singidunum.[137] By water, Crete, Cyprus and Sicily were key naval points and the main ports connecting Constantinople were Alexandria, Gaza, Caesarea and Antioch.[138] The Aegean sea was considered an internal lake within the Empire.[136]

Government

Governance

The emperor was the centre of the whole administration of the Empire, who the legal historian Kaius Tuori has said was "above the law, within the law, and the law itself"; with a power that is difficult to define[c] and which does not align with our modern understanding of the separation of powers.[147][148][149] The proclamations of the crowds of Constantinople, and the inaugurations of the patriarch from 457, would legitimise the rule of an emperor.[150] The senate had its own identity but would become an extension of the emperor's court, becoming largely ceremonial.[151]

The reign of Phocas (r. 602–610) was the first military overthrow since the third century, his reign also being one of 43 emperors violently removed.[152] The historian Donald Nicol states that there were nine dynasties between Heraclius in 610 and 1453, however, for only 30 of those 843 years was the Empire not ruled by men linked by blood or kinship which was largely due to the practice of co-emperorship.[153]

As a result of the Diocletianic–Constantinian reforms, the Empire was organised into Praetorian prefectures and the army was separated from the civil administration.[154] From the 7th century onwards, the prefectures became provinces and were later divided into districts called themata governed by a military commander called a strategos who oversaw the civil and military administration.[155]

In earlier times, cities had been a collection of self-governing communities with central government and church representatives, whereas the emperor focused on defense and foreign relations.[156] The Arab destruction primarily changed this due to constant war and their regular raids, with a decline in city councils and the local elites that supported them.[157] The historian Robert Browning states that due to the Empire's fight for survival, it developed into one centre of power, with Leo VI (r. 886–912) during his legal reforms formally ending the rights of city councils and the legislative authority of the senate.[158]

Diplomacy

According to the historian Dimitri Obolensky, the preservation of civilisation in eastern Europe was due to the skill and resourcefulness of the Empire's diplomacy, and that imperial diplomacy is one of its lasting contributions to the history of Europe.[159] The Empire's longevity has been said to be due to its aggressive diplomacy in negotiating treaties, the formation of alliances, and partnerships with the enemies of its enemies, notably seen with the Turks against the Persians or riffs between states like the Umayyads in Spain and the Aghlabids in Sicily.[160] Diplomacy often involved long-term embassies, hosting foreign royals as potential hostages or political pawns, and overwhelming visitors with displays of wealth and power (with deliberate efforts that word of it would travel).[161] Other tools in diplomacy included political marriages, bestowing titles, bribery, differing levels of persuasion, and leveraging intelligence as attested in the ‘Bureau of Barbarians’ from the 4th century and which is likely the first foreign intelligence agency.[162]

Ancient historian Michael Whitby claims diplomacy in the Empire following Theodosius I (r. 379–395) contrasted sharply with that of the Roman Republic, emphasizing peace as a strategic necessity.[163] Even when it had more resources and less threats in the 6th century, the costs of defense were enormous;[164] foreign affairs had become more multi-polar, complex and interconnected;[165] further the challenges in protecting the empire's primarily agricultural income as well as numerous aggressive neighbours made avoiding war a preferred strategy.[166] Between the 4th and 8th centuries, diplomats leveraged the Empire's status as Orbis Romanus and sophistication as a state, which influenced the formation of new settlements on former Roman territories.[167] Byzantine diplomacy drew fledgling states into dependency, creating a network of international and inter-state relations (the oikouménē) dominated by the Empire, utilising Christianity as a tool.[168] This network focused on treaty-making, welcoming new rulers into the family of kings, and assimilating social attitudes, values, and institutions into what Evangelos Chrysos has called a "Byzantine Caliphate".[169] Diplomacy with the Muslim states, however, differed and centred on war-related matters such as hostages or the prevention of hostilities.[170]

The primary objective of diplomacy was survival, not conquest, and it was fundamentally defensive or as Dimitri Obolensky has claimed "defensive imperialism", shaped by the Empire's strategic location and limited resources.[171] Historian James Howard-Johnston states a change in policies by emperors in the 9th and early 10th centuries was the basis for future activity.[172] This change involved halting, reversing, and attacking Muslim power; cultivating relations with Armenians and Rus; and subjugating the Bulgarians.[172] Telemachos Lounghis notes that diplomacy with the West became more challenging from 752/3 and later with the Crusades, as the balance of power shifted.[173] Historian Alexander Kazhdan claims the number and nature of the Empire's neighbours also changed significantly, making the Limitrophe system (satellite states) and the principle of unbalanced power less effective and eventually abandoned.[174] This meant by the 11th century, the Empire had changed this core diplomatic principle to one of equality, and Byzantine diplomacy evolved instead to solicit and utilise the emperor's presence.[175]

Complex diplomatic manoeuvring is how Michael Palaiologos managed to recover Constantinople in 1261 and its statecraft is what allowed the weakened Empire to act like a great power of the past in the 13–14th centuries.[176] The historian Nikolaos Oikonomides states that the Constantinople patriarch elevated the emperor's credibility, during this challenging time as the Empire battled militant Islam geographically and Latin Christians economically; and ultimately, it was its efficient foreign relations that kept the state alive in this late era and not anything else.[177]

Law

Roman law has its origins in the Twelve Tables and evolved mainly through the annual Praetorian Edict and the opinions of educated specialists called Jurists.[178] Hadrian (r. 117–138) made the Praetorian Edict permanent and ruled that if all the Jurists agreed on a legal point, it would be considered law.[179] The law eventually became confusing due to conflicting sources, and it was not clear what it should be.[180] Efforts were made to reduce the confusion, such as two private collections collating the imperial constitutions since Hadrian's reign, the Codices Gregorianus and the Hermogenianus, which were developed during the reign of Diocletian (r. 284–305).[181]

Eventually, an official reform of Roman law was initiated by the East, when Theodosius II (r. 402–450) elevated five Jurists to the role of principal authorities and compiled the legislation issued since Constantine's reign into the Codex Theodosianus.[182] This work was completed by what is collectively known today as the Corpus Juris Civilis, when Justinian I (r. 527–565) commissioned a complete standardisation of imperial decrees since Hadrian's reign, and also incorporated a comprehensive collection of Jurists' opinions, resolving conflicts to create a final authority.[183] This work was not restricted in its scope to just civil law, but also covered the power of the emperor, the organisation of the Empire and other matters now classified as public law.[184] After 534, Justinian would legislate the Novellae (New Laws) in Greek as well, which legal historian Bernard Stolte proposes as a convenient breaking point to demarcate the end of Roman law and the start of Byzantine law. This division is proposed largely due to the legal heritage of Western Europe coming mostly from law written in Latin as transmitted through the Corpus Juris Civilis.[185][186]

The researcher Zachary Chitwood claims that the Corpus Juris Civilis was inaccessible in Latin, particularly in the Empire's provinces.[187] There was also a stronger association of Christianity with the law, after people questioned how the law was developed and used following the 7th century Islamic conquests.[188] Together, this created the backdrop for Leo III (r. 717–741) to develop the Ecloga, 'with a greater view of humanity'.[189] The three so-called leges speciales (the Farmers’ Law, the Seamen’s Law, and the Soldiers’ Law) were derived from the Ecloga, which Zachary Chitwood claims were likely used on a daily basis in the provinces as companions to the Corpus Juris Civilis.[190] The Macedonian dynasty started their reform attempts with the Procheiron and the Eisagoge to replace the Ecloga due to its associations with iconoclasm, but also noteworthy because they show an effort to define the emperor's power according to the prevalent laws.[191] Leo VI (r. 886–912) achieved the complete codification of Roman law in the Greek language with the Basilika, a monumental work consisting of 60 books, and that became the foundation of all subsequent Byzantine law.[192] The Hexabiblos, published in 1345 by a jurist, was a law book in six volumes compiled from a wide range of Byzantine legal sources.[193]

The Roman and Byzantine law codes form the basis of the modern world's civil law tradition, underlying the legal system of Western and Eastern Europe, Latin America, African nations like Ethiopia, the countries that follow Common law, with ongoing debates about its impact on Islamic countries.[194][195][196] As an example, the Hexabiblos was the basis of Greece's civil code until the mid-20th century.[197] Historians used to think that "there was no continuity between Roman and Byzantine law", but this view has now changed due to new scholarship.[198][199]

Flags and insignia

Constantine (r. 306–337) introduced the Labarum, initially for the army, which was a pole with a transverse bar forming a cross, with the monogram of Christ, also known as the Chi Rho.[200] It later came to represent the emperor and was used by his successors for legitimisation and is known to have had usage up until the reign of Nikephoros II Phokas (r. 963–969).[201] By the late fourth and early fifth centuries, the Chi Rho Christogram, the monogrammatic cross also known as the tau-rho, and the cross were the most prominent Christian signs that could be seen, with the labarum-cross becoming the main banner during the Theodosian period.[202]

Art historian Andrea Babuin claims that the Roman Eagle was a symbol that was in continuous usage by the military until the 6th century, with one or two eagles likely representing the emperor through all reigns.[203] Heraldic flag's would later be adopted, but the lack of evidence makes it a challenge to confidently identify what was the most prominent.[204] Historian Alexandre Soloviev considers the Double-headed eagle to be an emblem of the Komnenoi, and the tetragrammatic cross of the Palaiologoi.[205] The double-headed eagle is more confidently attested as a symbol of the emperor in the late era when Andronikos II Palaiologos used it in 1301, but Babuin also says that it never was exclusive to the Empire as other contemporary empires also used it.[206][207] The tetragrammatic cross was a state symbol during the Palaiologoi, which has a four-fold symmetrical representation of the Greek letter Beta (also interpreted as firesteels), with continued debate by historians on what it means.[208][209]

Military

Army

In the 5th century the East was fielding five armies of ~20,000 each in two army branches: stationary frontier units (limitanei) and mobile forces (comitatenses).[210] The historian Anthony Kaldellis claims that the fiscally stretched Empire could only handle one major enemy at a time in the 6th century.[211] The Islamic conquests between 634 and 642 led to significant changes, transforming the 4th-7th centuries field forces into provincialised militia-like units with a core of professional soldiers.[212] The state shifted the burden of supporting the armies onto local populations and during Leo VI (r. 886–912) wove them into the tax system, with provinces evolving into military regions known as themata.[213] Despite many challenges, the historian Warren Treadgold states that the field forces of the Eastern Empire between 284 and 602 were the best in the western world, while the historian Anthony Kaldellis believes that during the conquest period of the Macedonian dynasty (r. 867–1056), they were the best in the empire's history.[214]

The military structure would diversify to include militia-like soldiers tied to regions, professional thematic forces (tourmai), and imperial units mostly based in Constantinople (tagmata).[215] Foreign mercenaries also increasingly became employed, including the better-known tagma regiment, the Varangians, that guarded the emperor.[216] The defence-orientated thematic militias were gradually replaced with more specialised offensive field armies but also to counter the generals who would rebel against the emperor.[217] When the Empire was expanding, the state began to commute thematic military service for cash payments: in the 10th century, there were 6,000 Varangians, another 3,000 foreign mercenaries and when including paid and unpaid citizen soldiers, the army on paper was 140,000 (an expeditionary force was 15,000 soldiers and field armies seldom were more than 40,000).[218]

The thematic forces faded into insignificance—the government relying on the tagmata, mercenaries and allies instead—and which led to a neglect in defensive capability.[219] Mercenary armies would further fuel political divisions and civil wars that led to a collapse in the Empire's defence and resulting in significant losses such as Italy and the Anatolian heartland in the 11th century.[220] Major military and fiscal reforms under the emperors of the Komnenian dynasty after 1081 re-established a modest-sized, adequately compensated and competent army.[221] However, the costs were not sustainable and the structural weaknesses of the Komnenian approach—namely, the reliance on fiscal exemptions called pronoia—unraveled after the end of the reign of Manuel I (r. 1143–1180).[222]

Navy

The navy dominated the eastern Mediterranean and were active also on the Black Sea, the Sea of Marmara, and the Aegean.[223] Imperial naval forces were restructured to challenge Arab naval dominance in the 7th century, and would later cede its own dominance to the Venetians and Genoans in the 11th century.[224] The navy's patrols, in addition to chains of watchtowers and fire signals that warned inhabitants of threats, created the coastal defense for the Empire and were the responsibility of three themes (Cibirriote, Aegean Sea, Samos) and an imperial fleet that consisted of mercenaries like the Norsemen and Russians that later became Varangians.[225]

A new type of war galley, the dromon, appeared early in the sixth century.[226][227] A multi-purpose variant, the chelandia, appeared during the reign of Justinian II (r. 685–711) and could be used to transport cavalry.[228] The galleys were oar-driven, designed for coastal navigation, and are estimated to be able to operate for up to four days at a time.[229][230] They were equipped with apparatus to deliver Greek fire in the 670s, and when Basil I (r. 867–886) developed professional marines, this combination kept a check on Muslim raiding through piracy.[231] The dromon were the most advanced galleys on the Mediterranean, until the 10th century development of a dromon called a galeai and which superseded dromons with the development of a late 11th century Western (Southern Italian) variant.[232]

Late era (1204–1453)

The rulers of the Empire of Nicaea that retook the capital and the Palaiologos that ruled until 1453, built on the Komnenian foundation initially with four types of military units—the Thelematarii (volunteer soldiers), Gasmouloi and the Southern Peloponnese Tzacones/Lakones (marines), and Proselontes/Prosalentai (oarsmen)—but similarly could not sustain funding a standing force, largely relying on mercenaries as soldiers and fiscal exemptions to pronoiars who provided a small force of mostly cavalry.[233] The Fleet was disbanded in 1284 and attempts were made to build it back later but the Genoese sabotaged the effort.[234] The historian John Haldon claims that over time, the distinction between field troops and garrison units eventually disappeared as resources were strained.[235] The frequent civil wars further drained the Empire, now increasingly instigated by foreigners such as the Serbs and Turks to win concessions, and the emperors were dependent on mercenaries to keep control all the while dealing with the impact of the Black Death.[236] The strategy of employing mercenary Turks to fight civil wars was repeatedly used by emperors and always led to the same outcome: subordination to the Turks.[237]

Society

Demography

From the rule of Diocletian (r. 284–305) until the East's peak following Justinian's recovery of western territories in 540, the population could have been as high as 27 million, but would fall to as low as 12 million in 800.[238] Plague and loss of territories to the Arab Muslim invaders significantly impacted the Empire, but it recovered, and by the near end of the Macedonian dynasty in 1025, the population is estimated to have been as high as 18 million.[239] A few decades after the recapture of Constantinople in 1282, the Empire's population was in the range of 3–5 million; by 1312, the number had dropped to 2 million.[240] By the time the Ottoman Turks captured Constantinople, there were only 50,000 people in the city, which was one-tenth of its population in its prime.[241]

Education

Education was voluntary and required financial means to attend, with the most literate people being the ones associated with the church.[242] Reading, writing, and arithmetic were foundational subjects taught in primary education whereas Secondary school focused on the trivium and quadrivium as their curriculum.[243] The Imperial University of Constantinople, sometimes known as the University of the Palace Hall of Magnaura (Greek: Πανδιδακτήριον τῆς Μαγναύρας), was an educational institution that could trace its origins to 425 AD, when Emperor Theodosius II had established the Pandidakterion (Medieval Greek: Πανδιδακτήριον).[244] The Pandidakterion was re-established in 1046 by Constantine IX Monomachos who created the Departments of Law (Διδασκαλεῖον τῶν Νόμων) and Philosophy (Γυμνάσιον).[245][246]

Transition into an Eastern Christian empire

The granting of citizenship in 212 to all free men residing in its territories transformed the multi-lingual Roman Empire, expanding citizenship to a vast majority of its population and leading to a shift towards societal uniformity, particularly in its citizens' religious practices.[247][248][249] Diocletian's reforms significantly altered governmental structure, reach and taxation, and these reforms also had the effect of downgrading the first capital, Rome.[250] The Constantinan dynasty's support for Christianity, as well as the elevation of Constantinople as an imperial seat, further solidified this transformation.[251][252]

In the late 4th century, when the majority of the Empire's citizens were pagan, Theodosius built on previous emperors' bans and enacted many laws restricting pagan activities; but it would not be until Justinian in 529 when conversions would be enforced.[253] The confiscation of pagan treasures, diversion of funds, and legal discrimination led to the decline of paganism, resulting in events like the closure of schools of philosophy and the end of the Ancient Olympics.[d][256] Christianity was also aided by the prevalence of Greek, and Christianity's debates further increased the importance of Greek, making the emergent church dependent on branches of Hellenic thought such as Neoplatonism.[e][258] Despite the transition, the historian Anthony Kaldellis views Christianity as "bringing no economic, social, or political changes to the state other than being more deeply integrated into it".[259]

Slavery

During the third century, 10–15% of the population was enslaved (numbering around 3 million in the east).[260] Youval Rotman calls the changes to slavery during this period "different degrees of unfreedom".[261] Previous roles fulfilled by slaves became high-demand free market professions (like tutors), and the state encouraged the coloni, tenants bound to the land, as a new legal category between freemen and slaves.[262] From 294, but not completely, the enslavement of children was forbidden; Honorius (r. 393–423) would begin to free enslaved people who were prisoners of war, and from the 9th century onwards, emperors would free the slaves of conquered people.[263][264] Christianity as an institution had no direct impact, but by the 6th century it was a bishop's duty to ransom Christians, there were established limits on trading them, and state policies which prohibited the enslavement of Christians shaped Byzantine slave-holding from the 8th century onwards.[265] However, slavery persisted due to a steady source of non-Christians with prices remaining stable until 1300, when prices for adult slaves, particularly females, started rising.[266][267]

Socio-economic

Agriculture was the main basis of taxation and the state sought to bind everyone to land for productivity.[268] Most land consisted of small and medium-sized lots around villages, with family farms serving as the primary source of agriculture.[269] The coloni, once referred to as proto-serfs, were free citizens; however, their status remains a subject of historical debate.[270]

The Ekloge in 741 made marriage a Christian institution and no longer a private contract, and the institution's development correlated with the increased rights of slaves and the change in power relations.[271] Marriage was considered an institution to sustain the population, transfer property rights, support the elderly of the family; and the Empress Theodora had additionally said that it was needed to restrict sexual hedonism.[272] Women usually married at ages 15–20, and were used as a way to connect men and create economic benefit among families.[273] The average family had 2 children, with mortality rates around 40–50%.[274] Divorce could be done by mutual consent but would be restricted over time, for example, only being allowed if a married person was joining a convent.[275]

Inheritance rights were well developed, including for all women.[276] The historian Anthony Kaldellis claims that these rights may have been what prevented the emergence of large properties and a hereditary nobility capable of intimidating the state.[277] The prevalence of widows (estimated at 20%) meant that women often controlled family assets as heads of households and businesses, contributing to the rise of some empresses to power.[278] Women were major taxpayers, landowners, and petitioners to the imperial court, primarily seeking resolution for property-related disputes in the latter capacity.[279]

Women

Although women shared the same socio-economic status as men, they faced legal discrimination and had limitations in economic opportunities and vocations.[280] Prohibited from serving as soldiers or holding political office, and restricted from serving as deaconesses in the Church from the 7th century onwards, women were mostly assigned household responsibilities that were "labour-intensive".[281] They worked in professions, such as in the food and textile industry, as medical staff, in public baths, had a heavy presence in retail, and were practicing members of artisan guilds.[282] They also worked in disreputable occupations: entertainers, tavern keepers, and prostitutes; a class where some saints and empresses allegedly originated from.[283] Prostitution was widespread, and attempts were made to limit it, especially during Justinian's reign under the influence of Theodora.[284] Women participated in public life, engaging in social events and protests.[285] Women's rights would not be better in comparable societies, Western Europe or America until the 19th century.[286]

Language

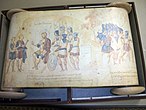

Right: The Joshua Roll, a 10th-century illuminated Greek manuscript possibly made in Constantinople (Vatican Library, Rome)

There was never an official language of the Empire, however, Latin and Greek were the main languages.[288] During the early years of the Roman Empire, knowledge of Greek had been useful to pass the requirements to be an educated noble, and knowledge of Latin was useful for a career in the military, government, or law.[289] In the east, Greek was the dominant language, a legacy of the Hellenistic period.[290] Greek was also the language of the Christian Church and trade.[291]

Most early emperors were bilingual but had a preference for Latin in the public sphere for political reasons, a practice that first started during the Punic Wars.[292] Classical languages expert Bruno Rochette claims Latin had experienced a period of spread from the second century BC onwards, and especially so in the western provinces, but not as much in the eastern provinces with a change due to Diocletian's reforms: there was a decline in the knowledge of Greek in the west, and Latin was asserted as the language of power in the east.[293]

Despite this, Greek's influence gradually grew in the government, beginning when Arcadius in 397 AD allowed judges to issue decisions in Greek, Theodosius II in 439 expanded its use in legal procedures, the first law in Greek was issued in 448, and when Leo I legislated in the language in the 460s.[294][295] Justinian I's Corpus Juris Civilis, a compilation of mostly Roman jurists, was written almost entirely in Latin; however, the laws issued after 534, from Justinian's Novellae Constitutiones onwards, were in both Greek and Latin, which marks the year when the government also officially began to use the former language.[296]

Historian Nikolaos Oikonomides states that Greek for a time became diglossic with the spoken language, known as Koine (later, Demotic Greek), used alongside an older written form (Attic Greek) until Koine won out as the spoken and written standard.[297] Latin fragmented into the incipient Romance languages in the 8th century, following the collapse of the Western Empire after the Muslim invasions broke the connection between speakers.[298][299] During the reign of Justinian (r. 527–565), Latin disappeared in the east, though it may have lingered in the military until Heraclius (r. 610–641).[300][301] Historian Steven Runciman claims contact with Western Europe in the 10th century revived Latin studies, and by the 11th century, knowledge of Latin was no longer unusual in Constantinople.[302]

Many other languages are attested in the Empire, not just in Constantinople but also at its frontiers.[303] They include Syriac, Coptic, Slavonic, Armenian, Georgian, Illyrian, Thracian, and Celtic; these were typically the languages of the lower strata of the population and the illiterate, who were the vast majority.[304] The Empire was a multi-lingual state, but Greek bound everyone, and the forces of assimilation would lead to the diversity of its peoples' languages declining over time.[305]

Economy

Following the split of the Western and Eastern Roman Empires, the West fell victim to political instability, social unrest, civil war, and invasions from foreign powers. In contrast, the Byzantines remained comparatively stable, allowing for the growth of a flourishing and resilient economy.[306] Institutional stability, such as the presence of a legal system, and the maintenance of infrastructure created a secure environment for economic growth.[307] In the 530s, the territory of the empire encompassed both a massive population of around 30 million people and a wide array of natural resources.[308] The Byzantines had access to resources such as abundant gold mines in the Balkans or the fertile fields of Egypt.[309] Large sections of the Byzantine population lived within the many urbanized settlements inherited from the previously unified Roman Empire. Constantinople, the capital of the empire, was the largest city in the world at the time; it housed at least 400,000 people.[310] These cities continued to grow during the 6th century, with evidence of massive construction projects suggesting that the Byzantine treasury remained strong.[311] During the 5th and 6th centuries, rural development continued alongside urban development; the number of documented agricultural settlements increased significantly during this period.[308] Although the reconquests of North Africa and Italy by Justinian I were expensive and draining campaigns, they reopened Mediterranean trade routes and parts of the Roman west were reconnected with the east.[306]

The Plague of Justinian caused significant demographic decline, negatively affecting the production and demand of the Byzantine economy; consequently, the Imperial treasury took a substantial hit. Economic downturn was worsened by conflicts with the Slavs, Avars, and Sassanids. Heraclius waged numerous campaigns to fend off the mounting threats to the empire, recovering the wealthy provinces of Syria, Egypt, and Palestine. However, these short-term fortunes were quickly reversed following the Arab conquests. Beginning in the 630s, the Arab wars with the Romans halved Byzantine territory, including rich provinces such as Egypt.[307] These collective disasters led to severe economic deterioration, culminating in large-scale deurbanization and impoverishment throughout the empire.[312] Demographic and urban decline sparked the destruction of trade routes, with trade reaching its lowest point by the 8th century.[307] Isaurian reforms and Constantine V's repopulation, public works, and tax measures marked the beginning of a revival that continued until 1204 despite territorial contraction.[313] From the 10th century until the end of the 12th, the Byzantine Empire projected an image of luxury; travellers were impressed by the wealth accumulated in the capital.[314]

The Fourth Crusade led to the disruption of Byzantine manufacturing and the commercial dominance of the Western Europeans in the eastern Mediterranean, both events which amounted to an economic catastrophe for the empire.[314] The Palaiologoi tried to revive the economy, but the late Byzantine state could not gain full control of either foreign or domestic economic forces. Eventually, Constantinople also lost its influence on the modalities of trade, price mechanisms, control over the outflow of precious metals and, according to some scholars, even over the minting of coins.[315]

The government attempted to exercise formal control over interest rates and to set the parameters for the activity of the guilds and corporations, where they held special interests. The emperor and his officials intervened at times of crises to ensure the stockpiling of provisions for the capital and to keep the prices of cereals affordable. Finally, the government often collected a part of the economic surplus through taxation, and put it back into circulation through either redistribution in the form of salaries to state officials or in the form of investment in public works.[316]

One of the economic foundations of Byzantium was trade, fostered by the maritime character of the empire. Textiles must have been by far the most important item of export; silks were certainly imported into Egypt and appeared also in Bulgaria and the West.[317] The state strictly controlled internal and international trade, and retained the monopoly of issuing coinage, maintaining a durable and flexible monetary system adaptable to the needs of trade.[316]

Daily life

Clothing

The court had a distinguishable dress, while certain conventions of clothing were observed by non-elite men and women.[318] Although no garments survive, Art historian Jennifer Ball claims that a fashion system began in the Empire many centuries before western Europe, and was not merely a textile industry, with trends driven by the provinces and not the capital which was more conservative.[319]

The imperial dress was centred around the loros, tzangia and crown which represented the Empire and the court.[320] The Loros derived from the trabea triumphalis, a ceremonial toga worn by consuls and was more prominent in the earlier period, showing a continuation of the traditions of the Roman Empire.[321] Jennifer Ball claims the chlamys was like a modern day business suit, which originated with the military and is a evolution of the paludamentum, and which the emperor also wore in the early period.[322] In the middle era, dresses replaced the tunic for women.[323] The late period sees the larger influence of non-Greek cultures on dress such as Italian (Genoese, Venetian), Turk (Ottoman) and Bulgarian.[324]

Cuisine

Byzantine cuisine still relied heavily on the Greco-Roman fish-sauce condiment garos, but it also contained foods still familiar today, such as the cured meat pastirma (known as "paston" in Byzantine Greek),[325] baklava (known as koptoplakous κοπτοπλακοῦς),[326] tiropita (known as plakountas tetyromenous or tyritas plakountas),[327] and the famed medieval sweet wines (Malvasia from Monemvasia, Commandaria and the eponymous Rumney wine).[328] Retsina, wine flavoured with pine resin, was also drunk, as it still is in Greece today.[329] "To add to our calamity the Greek wine, on account of being mixed with pitch, resin, and plaster was to us undrinkable", complained Liutprand of Cremona, who was the ambassador sent to Constantinople in 968 by the German Holy Roman Emperor Otto I.[330] The garos fish sauce condiment was also not much appreciated by the unaccustomed; Liutprand of Cremona described being served food covered in an "exceedingly bad fish liquor".[330] The Byzantines also used a soy sauce-like condiment, murri, a fermented barley sauce, which, like soy sauce, provided umami flavouring to their dishes.[331][332]

Recreation

Byzantines were avid players of tavli (Byzantine Greek: τάβλη), a game known in English as backgammon, which is still popular in former Byzantine realms and still known by the same name in Greece.[333] Byzantine nobles were devoted to horsemanship, particularly tzykanion, now known as polo. The game came from Sassanid Persia, and a Tzykanisterion (stadium for playing the game) was built by Theodosius II inside the Great Palace of Constantinople.[334] Emperor Basil I excelled at it; Emperor Alexander died from exhaustion while playing, Emperor Alexios I Komnenos was injured while playing with Tatikios, and John I of Trebizond died from a fatal injury during a game.[335] Other than Constantinople and Trebizond, other Byzantine cities also featured tzykanisteria, most notably Sparta, Ephesus, and Athens, an indication of a thriving urban aristocracy.[336] The game was introduced to the West by crusaders, who had developed a taste for it particularly during the pro-Western reign of Emperor Manuel I Komnenos.[337] Chariot races were popular and held at hippodromes across the empire. There were four major factions in chariot racing, differentiated by the colour of the uniform which they wore; the colours were also worn by their supporters. These factions were the Blues (Veneti), the Greens (Prasini), the Reds (Russati), and the Whites (Albati).[338]

Arts

Architecture

Influences from Byzantine architecture, particularly in religious buildings, can be found in diverse regions ranging from Egypt and Arabia to Russia and Romania. Byzantine architecture is known for the use of domes, and pendentive architecture was invented in the Byzantine Empire. In contrast to the basilica plans favored in medieval Western European churches, Byzantine churches usually had more centralized ground plans, such as the cross-in-square plan deployed in many Middle Byzantine churches.[339] They also often featured marble columns, coffered ceilings and sumptuous decoration, including the extensive use of mosaics with golden backgrounds. Byzantine architects used marble mostly as interior cladding, in contrast to the structural roles it had for the Ancient Greeks. They used mostly stone and brick, and also thin alabaster sheets for windows. Mosaics were used to cover brick walls and any other surface where fresco would not resist. Notable examples of mosaics from the proto-Byzantine era are at the Hagios Demetrios in Thessaloniki (Greece), the Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo and the Basilica of San Vitale, both in Ravenna (Italy), and the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. Christian liturgies were held in the interior of the churches, the exterior usually having little to no ornamentation.[340][341]

Art

| Byzantine culture |

|---|

|

Constantine's sponsorship produced an exuberant burst of Christian art and architecture, frescoes and mosaics for church walls, and hieroglyphic type drawings.[344] While classical and Christian culture did coexist into the seventh century, Christian imagery gradually replaced classical images, which had undergone a short revival under Julian the Apostate and in the Theodosian renaissance.[345]

In the 720s, the Byzantine Emperor Leo III banned the pictorial representation of Christ, saints, and biblical scenes. Bishops, the army and the civil service supported the emperors, while monks, sometimes at the cost of their lives, and the western papacy, refused to participate, leading to further separation between the East and West.[347][348] Lasting for over one hundred years, this ban led to nearly all figurative religious art being destroyed.[349] It wasn't until the tenth and early eleventh centuries that Byzantine culture fully recovered and Orthodoxy was again manifested in art.[350][351]